John Beck and Matthew Cornford

The Art Schools of the East Midlands

22 September – 2 December 2023

Exhibition preview: Thursday 21 September 6-8pm

This autumn Bonington Gallery presents The Art Schools of the East Midlands, the latest iteration of John Beck’s and Matthew Cornford’s ambitious Art School Project to locate and document the nation’s art school buildings or the sites upon which they once stood. The project combines photography, text, and archival materials to explore the histories and legacies of Britain’s art schools, and examine the vital role art schools have played, and continue to play, in the cultural and economic life of our towns and cities.

The twin Victorian engines of industrial ambition and social reform powered the British art school system, set up to deliver a skilled labour force for local industry – such as lace manufacture in Nottingham – and much needed educational opportunities to the newly enfranchised working class. Art schools combined practical training and exposure to culture, turning out skilled producers and discerning consumers well into the twentieth century.

By the mid-1960s there were still over 150 art schools in the UK, and ‘art school’ became a journalistic shorthand for creative innovation across arts, design, music and advertising. Yet at the peak of their influence on British cultural life, art schools in many towns and cities were already being amalgamated, reorganised and rebranded as part of a drive to reshape education in the arts. Most art schools have long since been absorbed into larger institutions or faded away.

Bonington Gallery’s presentation focuses on the art schools of the East Midlands and features original photographic images of all the region’s art school buildings alongside displays of archival material. The striking grandeur of Derby School of Art’s Gothic Revival building currently stands empty, whilst the Waverley Building built in 1865 for Nottingham School of Art remains one of the few Victorian built art school buildings still actively used for teaching art – as part of Nottingham Trent University. The project is also, importantly, an investigation of our present moment, documenting the sites of former art schools which have been redeveloped or reused.

The exhibition and the accompanying series of talks and events aim to create a space for dialogue and debate, raising questions about the role of the arts and art education in relation to community, history, and identity, and the shifting complex role of cultural production and cultural labour in the contemporary environment.

The Art School Project was prompted by the discovery that the college both Beck and Cornford attended in the early 1980s, Great Yarmouth College of Art and Design, was disused and up for sale. Evolving over 15 years the project takes the form of a series of regionally focused exhibitions. Their work on the West Midlands was recently shown at the New Gallery Walsall, and the North West iteration of the project was exhibited in Liverpool, Bury and Rochdale. The project is documented on Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/theartschoolproject/

John Beck and Matthew Cornford studied at Great Yarmouth College of Art and Design (now social housing) in the early 1980s and have served time, as students and members of staff, in colleges and universities across the country. John currently teaches literature and visual culture at the University of Westminster (incorporating what was once Harrow School of Art), and Matthew teaches fine art the University of Brighton (formerly Brighton School of Art).

Please contact Sarah Ragsdale sarah@sarahragsdalepr.co.uk

We are excited to announce details of the three gallery exhibitions that will form part of our 2023/24 programme, launching in September 2023.

Don’t forget to sign up to our mailing list to be first to hear about upcoming exhibition launches, tours and events for our next season.

John Beck and Matthew Cornford: The Art Schools of the East Midlands

Open: Friday 22 September – Saturday 2 December, 2023

Preview: Thursday 21 September, 6–8 pm

Featuring new photographic work depicting all the art school buildings of the East Midlands, or the sites upon which they stood, this exhibition aims to celebrate and encourage critical reflection on the place of art schools and art education in the region past, present and future.

The ‘Art School Project’ is an art and research collaboration that explores the history of the British art school system, its regional variations, educational and political contexts, and vital cultural legacies. Beck and Cornford’s photographic survey of the art schools of the North West was exhibited at Liverpool Bluecoat (2018), Bury Art Museum (2019) and Rochdale Touchstones (2021). Recent work on the West Midlands was shown at the New Art Gallery Walsall (February – July 2023) and a public artwork, commissioned by Meadow Arts and Hereford College of Arts, opened in Hereford June 2023.

John Beck is a writer and a Professor in the School of Humanities at the University of Westminster.

Matthew Cornford is an artist and Professor of Fine Art at the University of Brighton.

Instagram: The Art School Project

Onyeka Igwe – history is a living weapon in yr hand

Open: Saturday 13 January – Saturday 2 March, 2024

Preview: Friday 12 January, 6–8 pm

Onyeka Igwe is a London born and based moving image artist and researcher. Her work is aimed at the question: how do we live together? She is interested in the prosaic and everyday aspects of black livingness and exploring overlooked histories.

She was nominated for the 2022 Jarman Award, MaxMara Artist Prize for Women 2022-24, awarded the 2021 Foundwork Artist Prize, 2020 Arts Foundation Futures Award for Experimental Short Film and was the recipient of the Berwick New Cinema Award in 2019.

Artist website: https://onyekaigwe.com/

Film London Profile: https://filmlondon.org.uk/profile/onyeka-igwe

MoMa PS1 exhibition: https://www.momaps1.org/programs/182-onyeka-igwe

Osheen Siva

Open: Saturday 16 March – Saturday 4 May, 2024

Preview: Friday 15 March, 6–8 pm

Osheen Siva is an artist, illustrator and muralist, currently based in Goa. Through the lens of surrealism, speculative fiction and science fiction and rooted in their Dalit and Tamil heritage, Siva imagines new worlds of decolonized dreamscapes with mutants and monsters and narratives of queer and feminine power. They work in a variety of mediums including immersive media, installations, performance art, public art and digital illustration.

Past clients have included The New York Times, Adult Swim, Meta, Apple, Gucci, Adi Magazine, Absolut, Dr. Martens, Decolonize Fest among others.

Artist website: https://osheensiva.com/

It’s Nice That: https://www.itsnicethat.com/articles/osheen-siva-illustration-140721

Hyperallergic: https://hyperallergic.com/810814/coasting-the-topography-of-south-asian-futurisms/

We are delighted to announce that applications are now open for South London Gallery’s (SLG) annual post-graduate residency for 2023/24.

The residency will culminate in a solo exhibition at SLG in March 2024, and will tour to Bonington Gallery in January 2025.

What is the residency?

The Postgraduate Residency is an open submission six-month residency at South London Gallery (SLG) and touring exhibition between SLG and Bonington Gallery at Nottingham Trent University.

The residency enables the production of a new body of work and a rare opportunity for an early-career artist to exhibit their work at the South London Gallery and Bonington Gallery. The residency is open to artists who have completed a period of self-directed, peer-led or postgraduate study between October 2022 and September 2023. This can include alternative, peer organised and non-accredited programmes from an institution, collective or art school in the UK, as well as an MA, MFA, PGDip, MRes.

Between October 2023 – March 2024, the recipient will receive the following:

● studio space in the SLG Fire Station;

● a £4,500 housing bursary to cover accommodation in London;

● a £5,000 artists fee and a £4,000 production budget to produce new work;

● mentoring sessions and studio visits from SLG staff, including the Director, Bonington Gallery staff, and other arts professionals;

● the opportunity to present a public event in response to their practice;

● a solo exhibition opening March 2024 in one of the SLG Fire Station galleries.

● the exhibition will tour to Bonington Gallery in January 2025, with potential for associated event(s) and partnerships with university researchers & staff.

The residency and exhibition at the South London Gallery and Bonington Gallery is generously supported by the Paul and Louise Cooke Endowment.

Criteria

To be eligible for the residency applicants must:

● have completed an undergraduate degree (anytime before 2022) and have undertaken a postgraduate period of study between October 2022 and September 2023, including MA, MFA, PGDip, MRes, alternative, peer organised and non-accredited programmes, in an arts discipline from a UK institution, collective or art school, including Northern Ireland, Republic of Ireland, Scotland and Wales;

● not be enrolled in full or part-time education for an undergraduate, postgraduate or equivalent programme;

● be a UK resident or EU resident with settled or pre-settled status, or hold a Graduate Route visa with the right to stay in the UK for the entire duration of the residency.

We are particularly interested in receiving applications from those based outside of London. Support for travel (within the UK) will be offered to those invited to interview.

To Apply

Please visit the South London Gallery website for more information and to fill in an application form.

All applications should be submitted by Monday 17 July 2023 at 12 midday. Applications received after this time will not be considered.

There will be open information sessions about the residency held on Zoom on Wednesday 12 July at 1 pm. Please email lily@southlondongallery.org to register attendance.

For Emily Andersen’s exhibition Somewhere Else Entirely, we commissioned an essay by Daniella Schreir, editor of the Feminist Film Journal Another Gaze.

“Will it be a man, will it be another woman, will it be myself?” poet Ruth Fainlight asks in the voice-over of Emily Andersen’s eleven-minute three-channel portrait film, Somewhere Else Entirely. She is referring to the notion of the “muse” and although it is not made explicit, this three-part question is one Fainlight first posed in reply to an interview at an earlier point in her career; one she is – aged ninety at the time of filming – now reflecting back on. Of course, the history of art has never cared to trace the figure of the muse in relation to the woman artist, largely because the latter has never been historicised properly, let alone mythologised. As art historian Penny Murray has it: ‘Man creates, woman inspires; man is the maker, woman the vehicle of male fantasy.’ Fainlight – a self-proclaimed feminist – nonetheless seems surprised by the confidence of her younger self: ‘At that time I said arrogantly, “My muse is myself.”

There is something refreshing about Somewhere Else Entirely in its relationship to the figure of the woman artist and constellations of influence. Now, of course, it is much more common to talk about influence than muses, and to tack this abstract, ineffable notion onto real figures. We can see this in our contemporary neoliberal feminist moment, in which the culture industries are excavating women “pioneers,” and giving them their (rightful, although sometimes cynically delineated) places in museum and gallery exhibitions, on the lists of publishing houses, and in film programmes. Somewhere Else Entirely might have represented an attempt to highlight Fainlight’s importance qua woman poet, or have used the film form as a vehicle through which to recast Fainlight as a neglected “icon” in her field (and Andersen certainly knows how to capture these, having taken portraits of women including Dame Zaha Hadid, Nan Goldin, Nico, Tracy Chapman, Helen Mirren and Whitney Houston across four decades as a photographer). Instead, there is a fundamental humility to the film on the part of both filmmaker and subject. Fainlight appears on-screen in her local park and at her home in West London. She prunes her houseplants, spins salad leaves, boils an egg, sorts through her papers, reads – and yes, writes. As well as being the elements that make up a life, these quotidian fragments make sense when read alongside her poetry. As Richard Carrington has it: ‘[Fainlight] finds strangeness and even mysticism beneath familiar surfaces. Domestic life often contains and reveals the most significant truths.’ Meanwhile, Fainlight’s voice, off screen, is edited into a monologue, and although it is obvious that she has been guided by Andersen’s questions (at times I think I can make out a non-verbal utterance that seems to come from the filmmaker) her speech feels unprompted.

The first few seconds of Somewhere Else Entirely plunge the viewer head-first into a psychoanalytical drama. On the middle screen, the poet appears at the end of a corridor and walks slowly towards the camera, as we hear on the voice-over:

“I’m alone in the house and suddenly feel the need to phone my mother.

But it’s decades since she died – and I don’t remember having this urge before…”

From the depths of the dream-world, Fainlight’s voice brings us into the concrete and pragmatic with a start. We realise that she has been quoting the first line of one of her poems (‘A Meeting with My Dead’), and instead of unpacking or analysing it, she begins to discuss the shaping of its form. Andersen, meanwhile, cuts away from the corridor and to several annotated pages. Fainlight’s hands gesticulate above them. “I’m already reaching the place of not knowing what I’m going to write next,” she says. And, a few moments later: “I only know what the poem is going to say when I’m writing it”. Throughout Somewhere Else Entirely, Fainlight hovers above and circles her practice, sometimes capturing the inability to describe how a poem is made: “I only discover what I’m going to say while writing it”, at others admitting her powerlessness: “I’m in the hands of the poem”.

Somewhere Else Entirely is the product of a coincidence. Alongside her photographic practice, Andersen teaches at Nottingham Trent University. During a train ride back to her London base in 2011, she came across a review of Fainlight’s New & Collected Poems, accompanied by a picture of the poet. Andersen realised she had seen this woman in her neighbourhood and took a clipping of the review. The next day at her local market, Andersen saw Fainlight and approached her with the proposition of a portrait. In Andersen’s telling, Fainlight wasn’t immediately convinced but emailed Andersen a few weeks later. A portrait was taken, a friendship emerged and then, over the following decade, a filmic portrait. The film represents an encounter in the longue durée, which seems pertinent to Fainlight’s practice, in which she can spend “months or even years” on a single poem. Nevertheless, the initial, delicate meeting between the women is, I think, detectable in Somewhere Else Entirely whose visual montage is shaped by Fainlight’s narration. At no moment does it seem as though the filmmaker is bending the poet’s words to her aesthetic desires.. In its form, it is as though Andersen has taken Fainlight’s practice as a cue for her moving portrait.

Daniella Schreir

When I Dare to be Powerful International Conference will bring filmmakers, artists, writers and activists together with conceptual thinkers and cultural theorists to answer pressing questions relating to voice as an agent of change.

The conference period begins on 26 April with a series on online talks and podcasts, and runs through to the one-day conference on 21 June 2023 – book a place here.

In Conversation with Ather Zia on Writing as a Powerful Tool to Amplify Female Voices in the Kashmir Conflict

Wednesday 26 April 2023

7 pm – 8 pm (BST), online

In Conversation with Jasmine Qureshi on Voice in Environmentalism, Queerness, and Trans Rights

Wednesday 10 May 2023

7 pm – 8 pm (BST), online

In Conversation with Jeff VanderMeer on Nonhuman Voices

Wednesday 24 May 2023

7 pm – 8 pm (BST), online

In Conversation with Tracey Lindberg on Indigenous Voice in Literature

Wednesday 7 June 2023

7 pm – 8 pm (BST), online

In Conversation with Ally Zlatar on ‘Voice’ as an Authentic and Vulnerable Artistic Expression and a Therapeutic Power

Wednesday 3 May 2023

In Conversation with Olivia Lopez Calderon on Cultural Identity and Dissonance

Wednesday 17 May 2023

In Conversation with Ja’Tovia Monique Gary on the Importance and Burden of Locating Self within the Filmic Space

Wednesday 31 May 2023

For all the information, please visit the conference website

This conference is made possible by generous funding and support provided by Midlands3/4Cities, New Art Exchange, NTU Postcolonial Studies Centre and Bonington Gallery.

Emily Andersen

Somewhere Else Entirely

25 March – 13 May 2023

Exhibition preview: Friday 24 March, 6-8 pm

“When I’m not writing poetry everything is okay, life’s fine, but it is not entire. Something is missing.” – Ruth Fainlight

This spring Bonington Gallery presents Somewhere Else Entirely a new three-screen video installation by the acclaimed photographer Emily Andersen featuring the American-born poet and writer Ruth Fainlight, who has become one of Britain’s most distinguished poets.

Ruth Fainlight was born in New York City in 1931 and moved to England when she was 15. During a lifetime dedicated to writing she has produced numerous collections of poetry, short stories, and translations. In 1959 she married the writer, Alan Sillitoe, and her many literary friendships included Sylvia Plath, Jane and Paul Bowles, and Robert Graves.

Andersen’s work is an intimate portrait of Fainlight, now aged 91, presenting fragments of the poet’s life. Taking inspiration from Renaissance triptychs and their depiction of different elements of the same subject across three panels, Somewhere Else Entirely captures Fainlight at her home in London, making notes, on her walks, and in the seaside town of Brighton where she spent her teenage years. Each image is carefully framed with a photographer’s eye for composition and detail – Fainlight walking along the corridor, her green cardigan against green foliage, the booklined walls – and intentionally moves at a gentle pace, sometimes almost appearing to be a series of still images.

In Somewhere Else Entirely Fainlight talks off-screen, revealing fascinating insights into her life, her creative process, and how she is ‘in the hands of the poem’. Her intensely visual poetry and fiction touch on themes of time, memory, and loss – and in her voiceover, she movingly recites her poem ‘Somewhere Else Entirely’ composed after the death of her husband.

Andersen has been a photographer for four decades. Her work includes interiors, architecture, and landscape but she is best known for her award-winning portraiture, capturing well-known faces including Nico, Peter Blake, and Helen Mirren. Somewhere Else Entirely is Andersen’s first completed video portrait and is inspired by her decade-long friendship with Fainlight. The exhibition also shares its title with Fainlight’s 2018 poetry collection which features Andersen’s photographs on the cover.

The 11 minute long, three-channel video, will be shown on a 10.5m wide curved screen within the gallery space. To accompany the exhibition there will be an in-conversation with Emily Andersen and Ruth Fainlight, and an evening of performative readings, using the work to reflect on the reciprocity of words and images, and the process of biography.

The launch of Somewhere Else Entirely in Nottingham is significant, as Fainlight’s husband Alan Sillitoe was famously from the city, and the couple met in a local bookshop. Andersen is Senior Lecturer in Critical and Visual Practice of Photography at Nottingham Trent University.

Emily Andersen

Somewhere Else Entirely (2023)

Funded by Bonington Gallery and Nottingham Trent University

Bonington Gallery is part of Curated & Created, NTU’s extra-curricular and public arts programme.

Emily Andersen is a London-based artist and graduate of the Royal College of Art. Her work has been exhibited in galleries including: The Photographers’ Gallery, London; The Institute of Contemporary Art, London; The Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa; The Scottish National Portrait Gallery, Edinburgh; The Barber Institute of Fine Arts, University of Birmingham; Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art; Jehangir Art Gallery, Mumbai; China Arts Museum, Shanghai; BOOKMARC Gallery, Tokyo; and LOWW Gallery, Tokyo, Japan.

A number of her portraits are in the permanent collection of The National Portrait Gallery, London. She has won awards including the John Kobal prize for portraiture. Her third book Another Place was published in 2023. She is a senior lecturer in theory and practice of photography at Nottingham Trent University.

Contact Sarah Ragsdale: sarah@sarahragsdalepr.co.uk

A conversation between Bonington Gallery’s director Tom Godfrey and artist and curator Cedar Lewisohn over email during October 2022.

Tom Godfrey: Hi Cedar, initially it’d be great if you could offer an introduction to your practice, including the mediums you utilise and the ideas you explore.

Cedar Lewisohn: I’m an artist, writer and curator. Curating is really my main ‘day job’, but for this conversation I’ll focus on my visual art, studio practise. But to be honest, all areas of my work feed into each other.

In the studio – my work is often centred around drawings, which I translate into wood carvings, books and publications. Recently, I’ve used the wood carvings as the basis to make a virtual space and moving images. The subject matter for the past five years or so has focused on reappropriating images from various museum collections. Often images related to African, ancient Egyptian or Mesopotamian collections in those museums. The idea of mixing the very analogue process of the wood carved images, and turning that into a virtual space really appealed to me.

TG: What constitutes your research – what types of things do you like to read, watch or listen to?

CL: I’m always researching in some way or another. I’ve spent lots of time over the past few years visiting historic museum collections, and sometimes speaking to curators, finding out about the history of objects, and how they came into the collection. I had no idea the debates about contested museum objects would explode into the public consciousness in the way they have over the last year or so, in the wake of Covid and Black Lives Matter.

In terms of what I read or watch, it’s very, very varied. I tend to listen to lectures and audio books. I like highbrow things as well as total trash. In my digital library right now, I’ve got Black Skin White Masks by Franz Fanon, Lucky Jim by Kingsley Amis, and I just really enjoyed David Olusoga’s Black and British: A Forgotten History. In terms of music, I flick between a bit of drill, like 67, lots of reggae and dub, like Scientist, also lots of bands I’ve been into over the years, like Autechre or Slowdive. I mean this list could go on for a very long time. It just depends on my mood and the day.

TG: As you mention above, your overall practice encapsulates several different strands, including artmaking, curating and writing. Can you talk about what it’s like to work across these different areas – what overlaps, connections or separations may exist?

CL: To be honest, everything just feeds into each other, and it just makes sense for me. Curating is very collaborative, and really the area of curating I’ve mainly been involved with is in institutions. I enjoy bringing art projects to audiences and doing projects at scale. There are lots of negotiations and relationships, but when it works out, it’s extremely rewarding. I worked on a project called Dub London a couple of years ago, and that really got me into the history of Jamaican music and soundsystem culture. I never really knew the difference between, say rocksteady and ska before. But I’m really into rocksteady now.

As part of that research, I became more interested in Patois and the language used in the lyrics of the music. So, in the first lockdown during the pandemic, I did a course on Patois with a Jamaican poet and teacher Joan Hutchinson. It was fascinating to learn about the history of the language and the meaning behind many phrases in Jamaican English. So that is where the title for the exhibition at Bonington comes from.

With my studio practice, in essence, it is quite a tactile process. It’s physical and centres around things I make with my hands. The research I do for curatorial projects often feeds into my studio practice. I mean, all the time I spend in historic museums looking at objects and re-drawing them, could be seen as a form of curating. I also do lots of different types of writing, from short stories and fiction to straight up writing about art and culture. Recently, I’ve been doing what I call ‘Rants’. They are short texts that are quite funny, and a place to vent. I have all these ‘notes’, that I was planning to use in longer texts. Again, it’s almost a curatorial thing, if I was visiting an artist’s studio, and they had all this writing, in the form of a few sentences, my advice to them would be, just show the texts as they are. So, I decided to take some of my own advice.

TG: I’m interested in the immediacy and boldness you employ when manoeuvring between the different medias in your practice. For example, going from a woodcut to a VR experience, and the ease at which you appear to move between these different platforms. Can you talk more about this please?

CL: I aways do a lot of things at once. So, it’s often about how the projects fit together conceptually. With the VR piece, it’s made using hundreds of scans of my woodcut prints. So, the idea is partly to creative a digital experience that is also quite handmade or analogue. It’s partly a daft idea that I’ve followed through with but I do think there is a difference between handmade moving image work and digital animation. If you look at early Disney animation for example, when the individual cells are hand drawn and coloured, they have an energy and beauty that is lost when the process is digitised. So, I wanted to take this idea, of bringing back the handmade to the virtual space. Obviously, it’s not very practical. But who wants practical art?

TG: I like what you say above “…if I was visiting an artist’s studio, and they had all this writing, in the form of a few sentences, my advice to them would be, just show the texts as they are. So I decided to take some of my own advice”. It seems as though you’ve been able to internalise some of the objectivity that being a curator often affords. This is usually applied to other people’s work, but here it seems that you are able to look at your work through the eyes of a different position. Is this fair to say, and what does being a curator bring to your art, and what does your art bring to your curating?

CL: I love making art and I love organising art projects. These are separate disciplines that relate to each other but are far from being the same thing. I think most artists have to have a certain self-criticality and ability to self-edit. I also think artists can often be great curators. For me, having quite a lot of institutional curatorial experience, this does feed into my studio work. Some of my research processes, looking at historic museum collections and objects, could easily been seen as a curatorial practice. In terms of my art influencing my curating… Sometimes it seems like 90 per cent of curating is bureaucracy – so it takes an artist to cut through and just say, “here’s a crazy idea, let’s do it…” Which does loosely fit my curatorial approach.

TG: Without giving too much away, could you talk a little about some of your ideas and thinking for the exhibition at Bonington. The title ‘Patois Banton’ appears to highlight the ease you have in mixing together different reference points in a respectfully irreverent and generative way.

CL: During one of the [Covid-19] lockdowns, for some reason I decided to do Patois lessons. Because my heritage is Jamaican, there is something slightly ridiculous about this. Imagine an English person wanting to have lessons in how to speak Cockney. But still, I couldn’t speak Patois, so I did some lessons. I found an amazing tutor in Jamacia, and we did the classes online. Joan Hutchinson, the tutor, is a poet in her own right, and takes the subject really seriously. It was great to dive into the subject. It was quite academic, looking the history of words, grammar, all sorts. But also, folk stories, songs, and lots of meaning behind these things. There is so much Patois used in the English language, in music and conversation. But people often don’t know the history and context of these words. ‘Banton’ is a word people might, or might not be familiar with, it just means storyteller, something like the griot, in West African tradition. So, Patois Banton seemed like a good title for the show.

TG: Some of the source imagery that you use for your drawings, I’m thinking of the Black Drawings that you produced whilst on residency at the Jan Van Eyck Academie in Maastricht, are dense monochrome renderings of paintings by European Expressionist painters (although I think you include a Basquiat in this series). What is it about this group of artists that you have chosen to reference, and, by reducing these works to a singular form of execution is there any potential commentary/criticism being paid towards the established and widely adopted, western-centric/European cannons within art-history?

CL: The Black Drawings series was an exploration with the European fascination with so-called ‘Primitivism’ from the first part of the 20th Century.

The series came about quite spontaneously but due to having time and freedom of being on a residency at Jan Van Eyck Academie, I was able to fully explore. Before starting at the JVA around 2014, I saw a Hannah Höch exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery in London. Some of her collages which included images of African women intrigued me, so I took a few photographs. Obviously, the Höch images inspire lots of questions around cultural appropriation, depictions of the black body by white artists and so on. It started a train of thought about huge numbers of Modernist artists, who had done the same thing. So, when I was in Maastricht at the JVA, I spent a lot of time visiting museums and collections in that region, places like Cologne, Brussels, Aachen, Liège.

I kept seeing more and more work, sometimes by quite surprising artists, who you would not associate with African imagery, such as Fernand Léger, or Francis Picabia, Lots of German Expressionists, The Blue Rider Group. They all had works with African influences. So, I just re-drew them, but almost entirely in black. It was my way of re-appropriating the works, or “stealing them back,” as I used to say at the time.

It was not a super critical attack on the artists I was looking at. I was not trying to “take them down”. I actually love many of the artists’ work I was looking at. It was more about pointing out this massive influence of African imagery on Modernist aesthetics.

TG: I like your reference to early animation, that would turn hand-drawn cells into cinematic films. It would be great if you could go into a little more detail about the relationship between your lino-cuts and VR experiences. It feels that the ‘gulf’ you present between these mediums is wider than early Disney, and I guess these chasms will only grow as technology develops.

CL: The link between early animation and the digital space is something I’ve been thinking about fairly recently. I was doing some curatorial research a few years ago into early film and moving image, which is what perhaps first sparked my interest.

When we look at early hand drawn animations, there is a certain magic in the movement of the images, that to me, seems lost when the process is digitised. It’s the analogue v. digital debate, I guess.

With visual material, I do think there is a certain aura that we subconsciously recognise when the human hand has made something. With AI art and image production, this is an area I think more and more people will become concerned with. If AI can an make any image or object that that can be imagined, what is the actual point of having a human do it? Humans are kind of a pain in the arse, in comparison to a nice subservient AI programme. AI programmes don’t need lunch breaks, they don’t ask for pay rises and so on.

So ultimately, I’m trying to think about analogue virtual spaces, that have to be handmade by me. It’s a slightly ridiculous proposition at this point, but with the virtual space that uses woodcut and lino prints in the exhibition, we can see a type of prototype of what I’m thinking about.

TG: Finally, I’d like to hear more about your use of the book format. Due to their scale, the experience of looking and ’reading’ becomes a very physical and shared experience. By showing drawings in this way, the viewer(s) can only experience 1-2 images at a time, and not the full series in one go around the walls of a gallery. As a comparison, Andy Warhol’s ‘Shadow Paintings’ come to mind for how they are shown at DIA Art Foundation, but they could almost be pages from a book – or maybe cells from an animation.

CL: Books and printed publications have been something I’ve always enjoyed as an alternative display space. Again, it’s mixing curatorial and studio practice. Playing with the scale of the books adds a level of drama and spectacle that I really enjoy. When you have these massive books, just the act of looking at them and turning the pages becomes a performance. It turns the act of looking into a physical experience. It also slows down the way it’s possible to view the images and pages. So, it asks a lot from the viewer. But books suit me as a medium. Books are somewhat undervalued as a medium right now, but I have a long-term self-belief that the appreciation for the medium will increase.

Catch Cedar’s exhibition Patois Banton in the gallery from 21 January – 11 March 2023.

Cedar and Jamaican writer and teacher Joan Andrea Hutchinson will be holding a free in-conversation event to discuss Jamaican Patois on Thursday 16 February.

Cedar Lewisohn

Patois Banton

21 January – 11 March 2023

Launch: Friday 20 January 6–8 pm

Bonington Gallery, Nottingham Trent University, Dryden Street, Nottingham. NG1 4GG

Patois Banton is a new exhibition by artist, writer, and curator Cedar Lewisohn, on show at the Bonington Gallery, Nottingham Trent University, from 21 January 2023.

The exhibition will be Lewisohn’s first UK solo exhibition outside of London and follows his critically acclaimed exhibition The Thousand Year Kingdom at the Saatchi Gallery and group exhibition Untitled at Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge, both in 2021. As a curator, Lewisohn produced the landmark Street Art exhibition at Tate Modern in 2008, and more recently the Dub London project at the Museum of London. He is currently the Curator of Site Design at Southbank Centre, London.

Lewisohn’s work uses drawing as the starting point for a practice that encompasses woodblock and lino prints, publications, performances, moving images, sound, VR experience, and the written word.

Over the past decade he has been researching and drawing objects relating to ancient African and Mesopotamian civilizations within museum collections, including the Benin Bronzes, which have become a touchstone in the discussion around global museums’ restitution of looted heritage.

In his prints Lewisohn mixes his depictions of works from ancient civilizations with symbols of contemporary British youth culture, such as sound system culture, dancehall, drill music and urban landscapes, to explore current social, ethical, and political issues. The mix of African, Jamaican and British histories, locations, myths, and hidden stories is central to Lewisohn’s work.

The exhibition’s title is a fusion of two words that offer further insight into Lewisohn’s practice and preoccupations. During the pandemic, Lewisohn took lessons in Patois – the English-based creole language spoken throughout Jamaica – from academic and poet, Joan Hutchison. He is interested in the migration of Patois back to the UK through its use in reggae and dancehall lyrics, and its integration into the slang of young urban Britain. Banton is the Jamaican word for storyteller. Combining these words highlights Lewisohn’s concern with Jamaican heritage from both a personal and historical perspective, and his desire to explore its ongoing influence on modern-day British culture.

The exhibition will present a range of large and small-scale works, some not exhibited before. It will include works from his acclaimed book The Marduk Prophecy – shown alongside a newly commissioned publication, and an interactive virtual space that explores Lewisohn’s fascination with mixing the handmade – in this case his woodblock prints – with digital technology.

To accompany the exhibition Bonington Gallery will publish a new compilation of poetry by the artist. ‘Office Poems’ features a selection of poems exploring the humour and mundanity of office life. Each poem will be published in English and Patois, with translations by Joan Hutchinson.

Bonington Gallery is part of Curated & Created, NTU’s extra-curricular and public arts programme.

Lewisohn (b. 1977, London) has worked on numerous projects for institutions such as Tate Britain, Tate Modern and The British Council. In 2008, he curated the landmark Street Art exhibition at Tate Modern and recently curated the Museum of London’s Dub London project. In 2020 he was appointed curator of Site Design for The Southbank Centre. He is the author of three books (Street Art, Tate 2008, Abstract Graffiti, Merrell, 2011, The Marduk Prophecy, Slimvolume, 2020), and has edited a number of publications. His work has been exhibited nationally and internationally for over twenty years and belongs to a number of collections. In 2015 he was a resident artist at the Jan Van Eyke Academie in Maastricht. Lewisohn has been included in numerous group exhibitions and had solo projects at the bonnefantenmuseum in Maastricht (2015), Joey Ramone, Rotterdam (2016), in VOLUME Book Fair at ArtSpace Sydney (2015) and Exeter Phoenix, (2017). Most recently he had a solo exhibition at Saatchi Gallery entitled The Thousand Year Kingdom in 2021 and participated in the group exhibition UNTITLED: art on the conditions of our time at Kettles Yard, Cambridge where his work was named by The Guardian as “the highlight of the show”.

Sarah Ragsdale sarah@sarahragsdalepr.co.uk

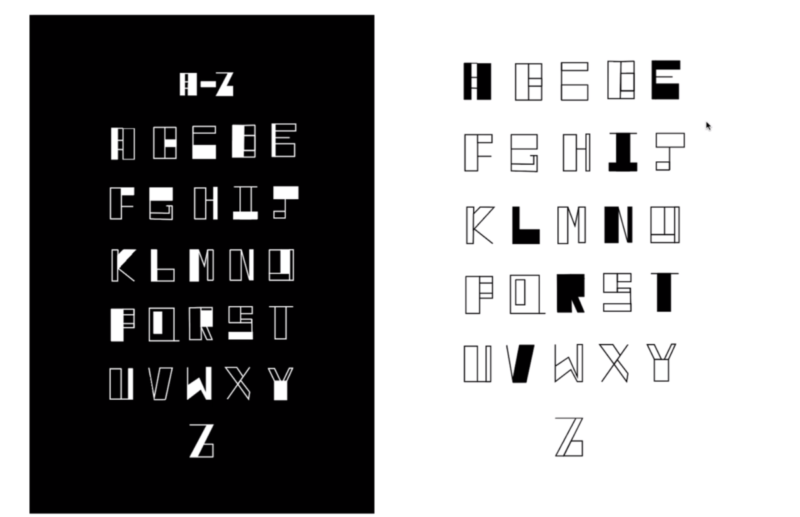

In response to our exhibition Stephen Willats: Social Resource Project for Tennis Clubs, NTU students on the Typography Optional Module created a typeface and re-imagined our exhibition invite. Over two half day sessions, they each created a typeface and type layout for the invite – we are excited to share some of their designs!

Click on them to see them full size

In response to our exhibition Andrew Logan: The Joy of Sculpture, NTU Students on the Typography Optional Module created a typeface and re-imagined our exhibition booklet and invite. The students had half a day on each exercise and came up with some fantastic responses!

We are excited to share a selection of them below:

Use the links below to have a look at their leaflets: