New romantics, futurists, or the ‘cult with no name’ took shape in the public eye through 1980, though it had been gestating as a look and pose in London after-hours dives, Bowie haunts and Essex soul-boy clubs a year or so earlier. It emerged as a club scene, pinned down by both a fashion movement away from identikit punk and a new music scene or genre. At the same time, it is one of those things that gets claimed more and more retrospectively by a select clique of people, conjured as a mythical yet minoritarian moment that retreats in time to a hallowed but disputed origin point.

Author Richard Evans shows with his recent work meticulously chronicling the electronic pop single how a music associated with new romantic began to establish itself from 1978 onwards. A new type of sound that moved beyond punk, Bowie and Roxy Music – electronic but edgier than Kraftwerk. Neo-dystopian synth debuts by the Human League, Throbbing Gristle and The Normal stood out as a genre yet to be named. It can be argued that the experimental music strand fell more under the banner of futurist, whilst the pomp and pantomime aspect was associated with new romantic, although the two scenes were (and still are) often conflated.

As something with a distinctive look and a claim to be a break with the past, there were certain moments that contoured new romantic’s rise out of the obscure underground. This mainly coincided with nightclubbing scene-leaders deciding to move from being clothes horses to starting bands and releasing records – not always a wise decision. Perhaps they should have done as Bruce McLean did in 1971 with his Nice Style project – a purely ‘pose band’. The scene’s self-elected house band Spandau Ballet had formed in late 1979 and featured on Janet Street Porter’s television programme 20th Century Box which showcased niche arts and music. Even though they were bonafide musicians, to start with they were close to McLean’s Nice Style, prioritising how they dressed, how they assembled, and how they articulated their concept with introductory avant-garde poetry by promoter and journalist Robert Elms.

New romantic’s move to the mainstream was accelerated through 1980 with a clutch of new magazines, Bowie’s ‘Ashes to Ashes’ video in August, Spandau Ballet charting in November, and Visage’s ‘Fade to Grey’ following in December. Of course, Adam and the Ants were in there as the first of this scene on Top of the Pops, though being tagged with kick-starting the new romantic scene is an accolade that has never sat well with Adam. This flurry of overtly visual activity in 1980 opened the floodgates in 1981 for a heavily commercialised scene and assault on the mainstream charts. We also got an approximate new genre of ‘synth-pop’, some three years after the Human League and others simultaneously set out their stalls.

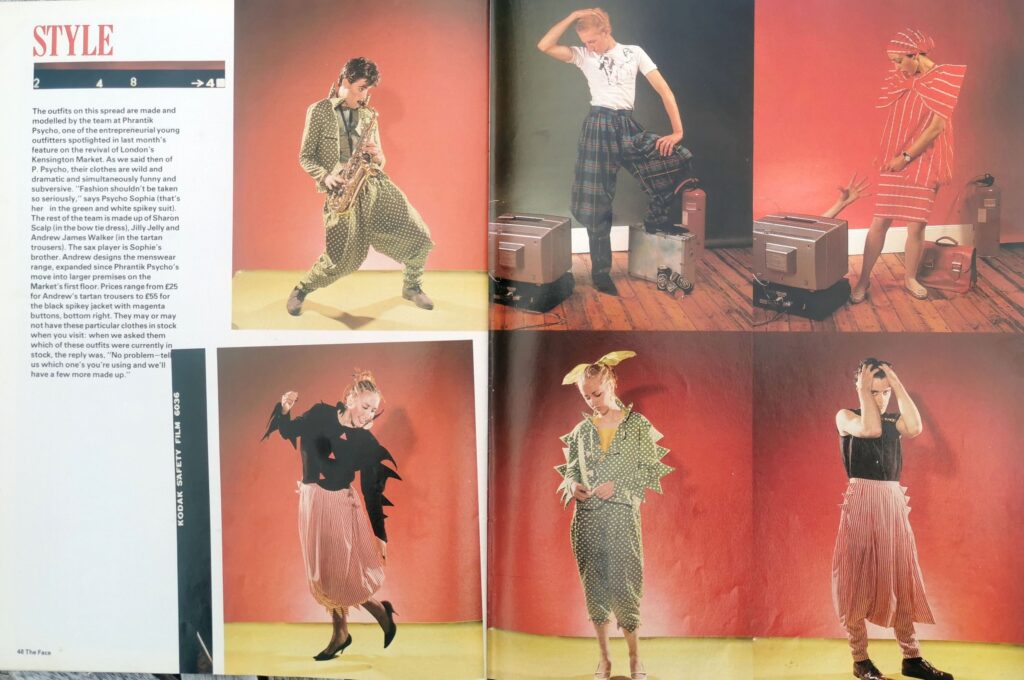

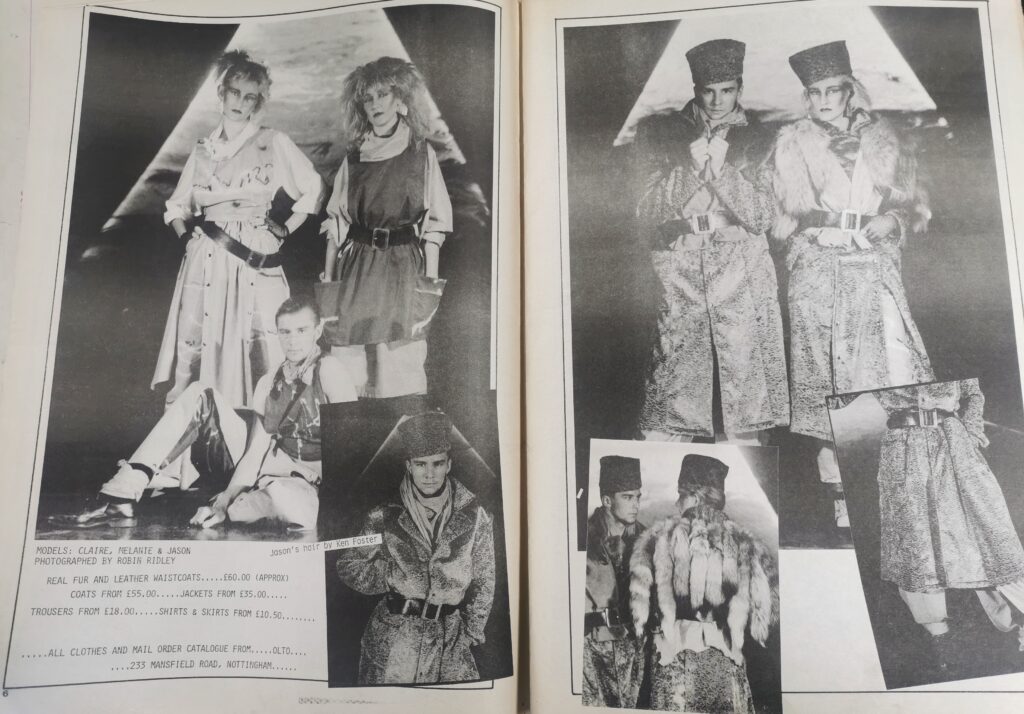

There was a huge emphasis on dressing up. New romantic clothing came from a mix of plundering costumiers and army surplus shops, having just enough skill to run up your own creations on a sewing machine, or having the inside track on a handful of experimental designers like Birmingham’s Kahn and Bell, London’s PX, or the small stalls dotted around Kensington Market such as Phrantik Psycho. In Nottingham, the incredible and confident efforts of Ollie and Tony Brack as Olto gave people a local option.

For the diehard participants there was a twin dynamic of exclusivity (how many people were ‘in the know’) and peacockery (how far you could push a look away from what previously existed). These came with their own dilemma and were easily prone to tipping points. Exclusivity is obviously undone by an encroaching mainstream awareness, and the dressing up aspect is in danger of falling into the simply absurd. Historically, many subcultures have an unwritten rule of style and looking sharp alongside adhering to certain codes and motifs. The new romantic movement was gradually pulled towards something resembling contemporary surrealism where anything goes, the crazier the better. In many ways it felt like alien territory, paving the way for figures like Leigh Bowery who pioneered a flipside of the more prescriptive and homogeneous club-cultural looks that marked out the end of the 80s (dungarees, Kickers, faux-ethnic prints, bandanas).

In terms of a more progressive music with a future-facing edge, the whole thing was boosted by DJ and industry rebel/mogul Stevo and his moves to set up a new home for independent electronic pop via his Some Bizzare label (he also provided the Futurist chart in Sounds from September 1980). Stevo was (and remains) a larger-than-life character who tirelessly promoted the futurist genre (though he never used that term), which was set slightly at odds to the more dressy-fixated new romantic scene. His background is well documented in Wesley Doyle’s 2023 book Conform to Deform and includes snippets about his time hosting a futurist night at the back-of-beyond Retford Porterhouse.

The Some Bizzare Album from early 1981 was very much the starting point of a collectivised new strain of awkward pop constructed through electronic means. Though many of the tracks had either a punk sensibility or abrasive non-conformist outlook, there was clearly a pop potential lurking in the margins. Bands like Soft Cell and Depeche Mode quickly shifted across from appearing on Some Bizzare to major label backing, effortlessly joining in the fashion chase of 1981 donning a different look each month; ski-jumpers, leather and chains biker boys, woodland elves, etc.

With new romantic going overground in late 1980 through multiple cover features in The Face and the arrival of Some Bizzare as a production line, it looked like 1981 would be set fair for various attempts to stretch this out. The scene moved beyond a simple clubbing and dressing up opportunity to incorporate bands doing PAs, gigs or even hastily cobbled together package tours such as the ‘2002 Review’ assembled by Classix Nouveaux. Following Stevo’s somewhat scattershot Electronic Indoctrination tour of 1980 there was a planned tour of Some Bizzare bands in early 1981 to celebrate the new album. This was abandoned after a number of chaotic, no-show gigs, though outfits like Naked Lunch and B-Movie (formed in Mansfield) would happily trudge the motorways of the UK bringing a new romantic fantasy world to exotic places like Retford Porterhouse, Dudley JBs, and Preston Warehouse.

In Nottingham the nightclub Rock City opened at the end of 1980. Though modestly ambitious in size and scope, it catered for many niche subcultures. As well as supporting the futurist scene with dedicated nights, it also promoted the underground break-dancing scene with numerous all-day events. It quickly gained a futurist reputation: Duran Duran (supported by B-Movie) played an early gig there in March 1981 (with a repeat in July), followed by the 2002 Review rolling in to town at the end of March fronted by the shaven-headed Sal Solo and his band of ex-X-Ray Spex members. Performance dancers Shock (with the robotic duo Tik and Tok) graced the stage in June, with a return one week later by Classix Nouveaux supported by Our Daughters Wedding – a band whose legacy has not aged well. Nottingham favourites Olto held a fashion shoot there, coinciding with the venue getting a new lighting system.

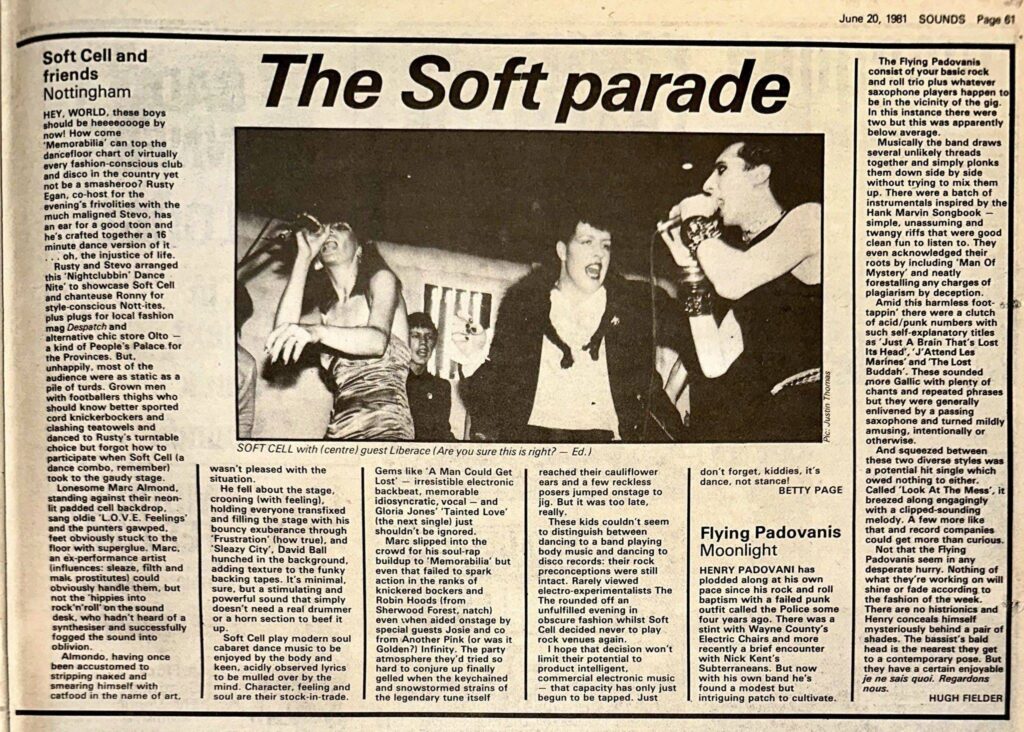

In June 1981 Rock City received a second visit from Leeds band Soft Cell. The duo, whose stage design ideas (including the padded cell) were created by student friend Huw Feather at Trent Poly, were still somewhat chaotic and art school. They were trying to break through after a handful of 1980 gigs, with the track ‘Memorabilia’ released to little attention, even though it is now seen as something of a classic. Soft Cell had already played Rock City in early April 1981, sharing the bill with B-Movie as the Nottingham and wider East Midlands futurist scene started to grow. They were back again in early June as the main act, with a gig in support of local scene newspaper Despatch. On the bill for the June event we also have ‘Ronny’ (who was described as a chanteuse), an early performance by The The, and then the bigwigs Stevo and Rusty Egan assembling a “Nightclubbing DanceNight” – effectively a coming together of the new romantic brand created by Egan and the futurist affront led by Stevo.

The night is reviewed in Sounds. The London-based journalist, making snide references to the “Peoples Palace for the Provinces”, is perhaps a little caustic and condescending, but the bit that stands out for me is the reference to “grown men with footballers thighs who should know better sported cord knickerbockers and clashing teatowels”. An aspect of this rang true on a personal level with my own brief (schoolboy) foray into the scene.

As with many subcultures, my way in was through a mix of music and looks. Some bands clearly looked good and prompted me in to buying a record, although looking good was no prerequisite to sounding good or having any musical ability. The new romantic music scene was often evidence of this. On the flipside, sometimes a record – a snatched moment on John Peel – stood out. There were post-punk records in this genre that excited me and made me want to dance, still sitting within my record collection – the first 12s from Heaven 17 released through 1981, the heart-racing synth pulse of Simple Minds ‘I Travel’ which dropped out of nowhere in October 1980. As I started to venture to nightclubs which catered for a non-mainstream scene, these records were still part of the playlist.

This interest in synth-pop prompted my first move away from a provincial punk look into something more fully formed and prescriptive – a brief dalliance with the new romantic scene. It was a look that I never managed to attain and was cobbled together from Derby’s Eagle Centre Market which had swapped second-rate punk standards like the tartan trousers and fluffy jumpers for third-rate new romantic clobber. There were purchases of surgeon-collar shirts, side-buttoning shirts and bright baggy trousers (aquamarine jumbo cords stick in my mind). And of course, pixie boots with trousers tucked in.

The seeds of my futurist phase were actually planted a little earlier. In spring 1980, in the midst of my O levels, I wanted to write to a band, so I chose Modern English. Their single ‘Gathering Dust’ had come to my attention by exemplifying a post-punk energy and innovation – chiming guitars, tribal drums, sweeping feedback effects, urgent vocals. It was partially a calculated decision, with me thinking that maybe not many other people would be writing to Modern English, so I had more chance of eliciting a response. This worked, and I had a few letters from them.

In May 1981 Modern English landed a support slot with Japan on their British tour. They told me this well in advance in a letter, and it appeared that they were also adopting a ‘classic’ futurist look. Japan were a big favourite on the early 1981 new romantic scene with their bouffant wedge haircuts, powdered faces and dandy clothes drawing from a Warholesque pop art palette. They had a background in the intelligent strand of glam – Roxy Music, Brian Eno – but this didn’t seem to go against their rise to popularity on the scene. New romantic did not exercise the tabula rasa cultural scorched earth policy of punk. They were promoting their new single ‘The Art of Parties’, hoping to break into the Top 40 for the first time. Later success would soon follow with the singles ‘Life in Tokyo’ and ‘Quiet Life’, purring with the swirls of synths and funky bass that had only been glimpsed on their earlier records.

The tour was scheduled to visit Rock City as part of the burgeoning futurist scene in the city. Modern English wrote to me, inviting me to attend. I was only 15, and there was no way on Earth I could look the required 18 to get into the venue who were renowned for having strict doormen. Wearing my best surgeon shirt and homemade jodhpurs (the old Birmingham bags with a line of press-studs to cinch in the lower legs), I caught the Barton bus to undertake the 15-mile journey. I was planning in advance and had saved up for a taxi home – none of my family had a car. A taxi was an extravagance, and I think this would have been the first time I’d be using one on my own.

Even though this occurred over 40 years ago, I recall strongly the queue, of being taken by surprise. It was full of male Japan clones but there was an absence of the otherworldliness or (possibly) softness that I anticipated and associated with the band through their magazine and television appearances. The soft pink lights and smoke machines of the studio mise-en-scene was obviously absent, replaced by the crepuscular gloom cut through with the bright white spots shining into the queue. It was raining, with sporadic storms. Instead of the ethereality of Japan it was hastily applied make-up running in the rain over stereotyped neck frills, offset by beer breath, body odour, stubble and gruff voices. This cultural incommensurability stuck with me; it wasn’t like the pages of a feature in The Face – an airbrushed perfection.

Unsurprisingly, the doormen never let me in. The band came to the door to try and reason, but it was never going to happen. They were running on a tight schedule so they bade me farewell and I saved on taxi fare by getting the last bus back to Derby. I treated myself to a burgundy asymmetric buttoning shirt the next day with the windfall.

In contemporary music historiography, the new romantic movement is heavily mythologised, locked down to a London-centric laser focus. Documentaries are in constant production and on endless repeat. The picaresque origin story and unravelling of new romantic has hardened into a reiterating script played out by a dwindling number of self-appointed and self-aggrandizing key figures. They age (inevitably) and somehow look less and less reliable or believable as storytellers. Tired eyes, balding hair, sunken and wrinkled faces, obesity – it kills the dream. Boy George, Marilyn, various Spandau Ballet members, Robert Elms, Princess Julia on autopilot, telling a seamless story of joy with the go-to anecdotes of Boy George as the pocket-pilfering cloakroom attendant and Steve Strange as stentorian doorman turning away Mick Jagger. The narrative script is akin to a theme park experience – tightly controlled and emotionally intact. The anachronism of their music and cultural statement is reversed, from being futuristic in the past, presenting something before its time, to being out of date in the present, clinging on to a redundant version of themselves from the past.

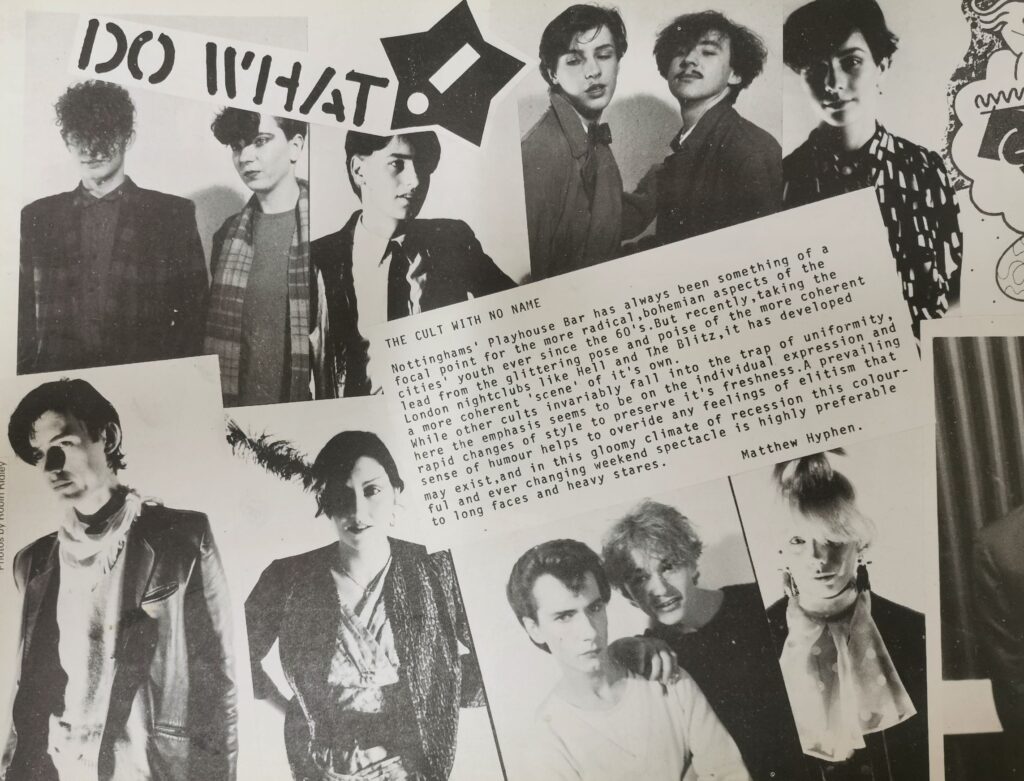

The protectiveness of the scene by a London journalist clique often led to sarcastic articles on provincial outposts of new romanticism. Such scenes were forever the butt of snidey and jokey remarks from the caption writers at i-D, laughing at ‘common people’ trying to look like Steve Strange. An exception was by the local journalist Matthew Hyphen writing in the third issue of i-D (February 1981). He covered the scene at the Playhouse bar, with an array of characters mugging for the camera and looking a little more swish and stylish than the apparent hordes donning Robin Hood tights and smocks at Rock City.

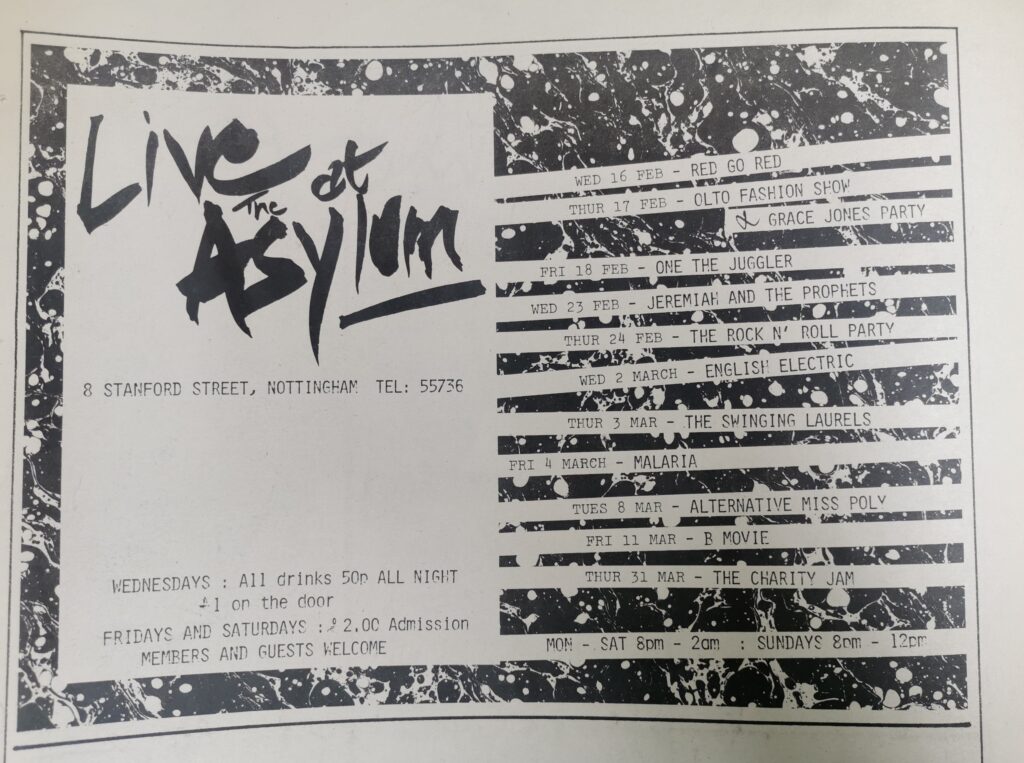

The clothes-and-pose-driven scene kept running in the city, mirrored over the border at Derby’s Blue Note. Despatchnewspaper thriving is evidence of this. By the time that Whispers rebranded to the Asylum at the end of 1982 and start of 1983, you can still see an array of new romantic or ‘dressy’ bands holding the fort. The synth-pop throb kept pulsing on.

– Ian Trowell