When you are conspicuously young, and venturing into the subcultural whirlpool, the suit is a hard look to pull off. On first glance the punk subculture seemed to eschew the wearing of suits, so it wasn’t a problem I had to face. Unless they were festooned with rips and zips, suits were not part of the fashion lexicon and remained the province of either smart dress or something worn by friends trying to get into over-18s discos. Suit-wearing hovered around the edge of new wave which offered an intriguing take on things but was always open to criticism due to the apparent watered-down status of the music and stance. Punk designed by a corporate board from a record label using musicians who had tried their luck in earlier genres. The ‘year zero’ rule ALWAYS had to be applied.

Then came post-punk, which passed the punk credentials test whilst also toying with the wearing of suits. Often this was a marker to distinguish itself from raw punk, though proto-synth-pop bands like Ultravox! managed to make suits look intriguing. Other bands who were broadening their music flirted with the suit (or blazer) look – plain styles such as worn by Simple Minds or Psychedelic Furs, or more adventurous looks sported briefly by Siouxsie and the Banshees when they bordered on a new romantic look.

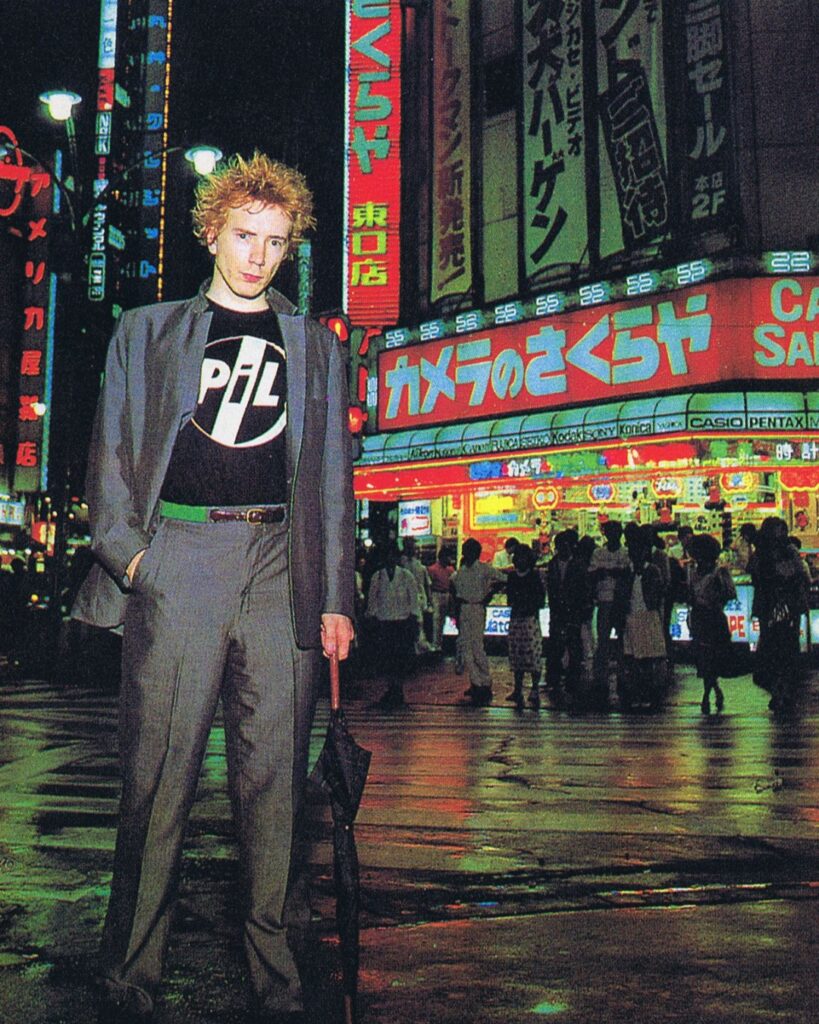

Public Image frontman John Lydon, in a move to distance himself from the grip of an over-subscribed look dictated by McLaren (and Westwood) took to wearing Caroline Walker suits, in a distinctive post-punk style. For the cover of his 1983 album Live in Tokyo, he looks simply incredible, resplendent in a shimmering silver-grey suit. It is misleading to think it is a deliberately drab or formal affair of suit-wearing and that Lydon’s pairing of it with a simple PiL tee (in black) and his orange spiked hair creates a punky clash of connotations. It is clearly a studied look. It has a sheen and cut that is almost classic early 80s, perhaps (whisper it) in the Duran style. The green belt is an important detail. As is the upturned collar on one side. That’s good, as Lydon cuts rough and goes against its stylistic rules. And not simply in a Miami Vice way. This picture stands the test of time.

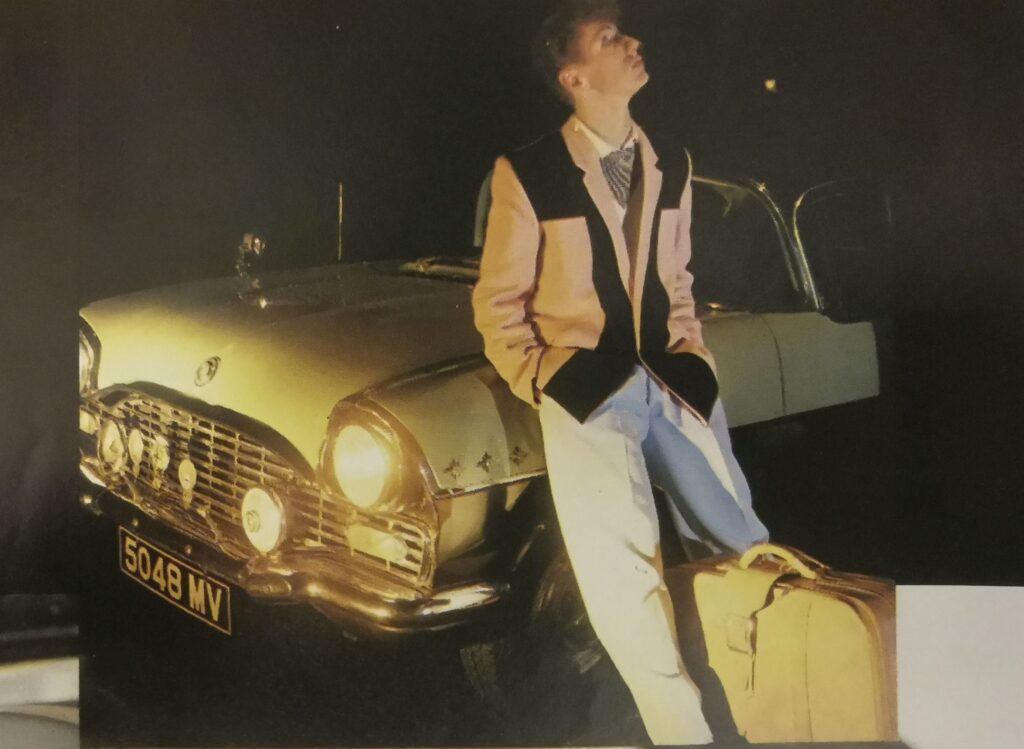

My first suit purchase was inspired by a neo-rockabilly fashion photoshoot of The Polecats in the March 1981 issue of The Face. Tim Polecat wears the Rock-a-Cha boxy jacket in contrast pink and black, leaning against an American car and looking up to the moon. For the knowing Polecats fan, there are probably at least four of their song titles in this ensemble and pose!

A similar jacket was also produced by G-Force, and I bought a version in mint green and black. It looked ok in the shop mirror, but by the time I got it home I was having serious doubts. I was young, and evidently non-debonair. The jacket was incredible to touch and smell, but was too swish, and the stiffened construction was made worse by my puny teenage body and home-made haircut. Rather than making me look older and wiser, it made me look younger. It reminded me of a peach pageboy suit I had to wear at a relation’s wedding when I was around eight years old. The photographs turned up recently as my parents were having a clear-out, but I’m loath to include them here. I don’t recall wearing the G-Force jacket, and I presume it was eventually thrown out when I left home.

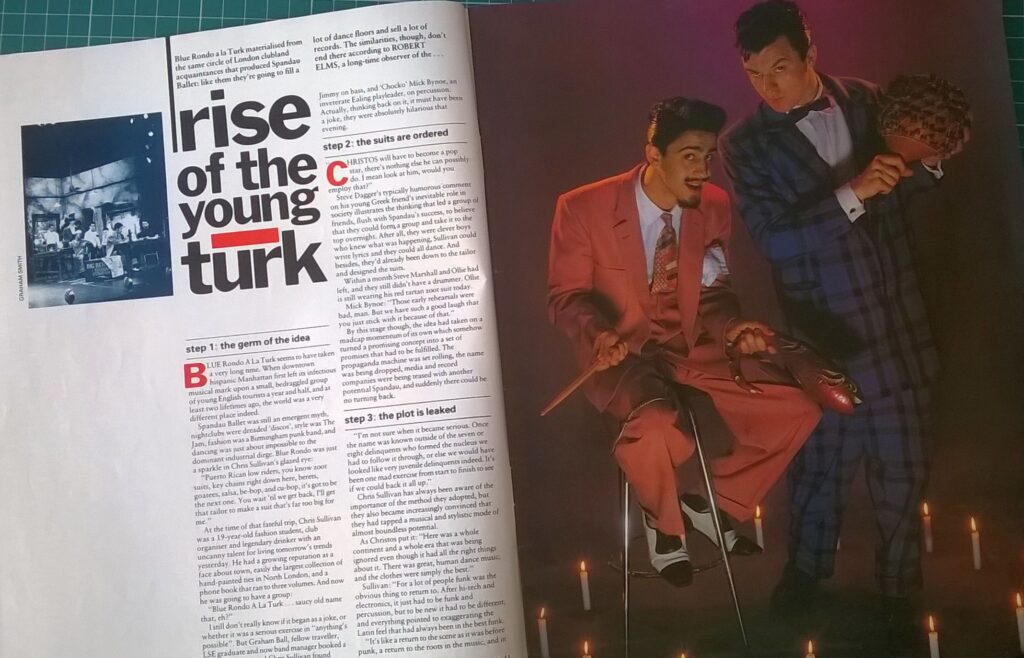

By summer 1981 something phenomenal happened: the zoot suit entered the subcultural arena and was seen very much as a must-have thing that worked across numerous scenes. Voluminous, high-waisted and worn with watch-chains, they were always a specialist thing and originally featured in The Face (September 1981). They were promoted and modelled by the ultra-stylish band Blue Rondo a la Turk – competing heirs to the crown of the go-to underground new romantic house band now that Spandau Ballet had sailed off into the charts to churn out endless hits under the guise of soul.

Zoot suits, a revival from the 50s, were garish and cut long, the jackets draping low and the trousers spilling out in a cartoon style. They were generally photographed in a postmodernist 50s sleazy or steamy setting, with the models nominally constricted by the plethora of fabric surface area to a bolt upright stance or perhaps an elbow leaning against an American car or retro jukebox. There was always an excess of greased and glistening pompadour hairstyles to match the suits. Keep clear of naked flames.

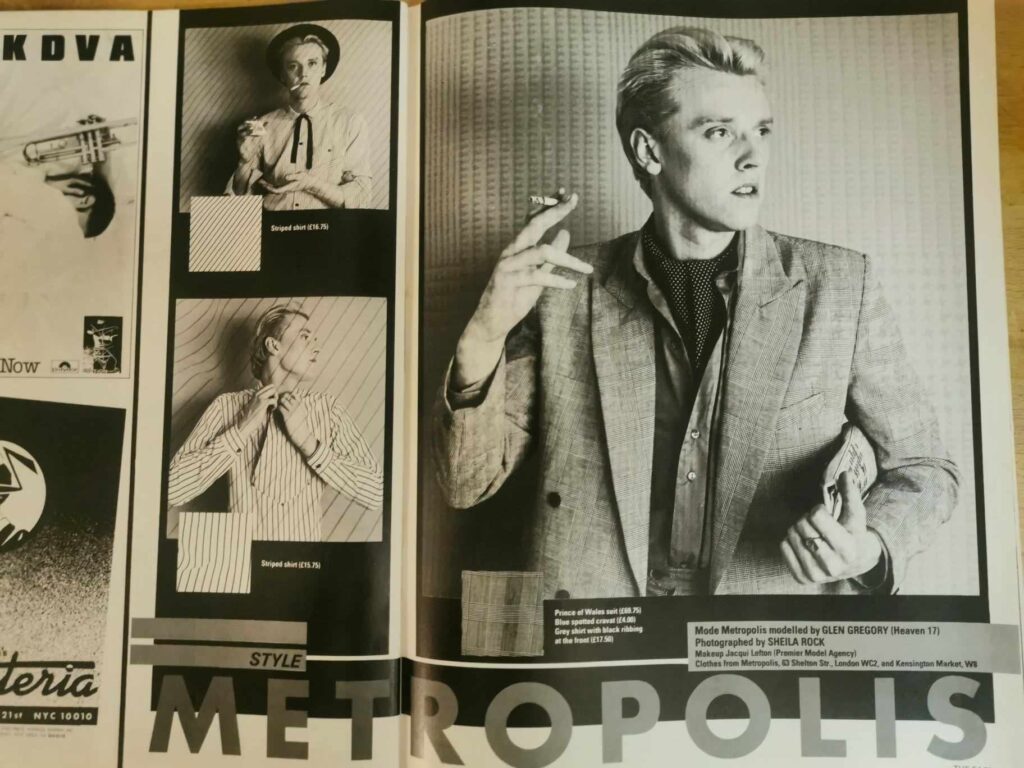

As 1981 concluded thematic suits came thick and fast. The conceptual electronic pop band Heaven 17 dressed as young business executives with pinstripe suits. When we look back on the decade and condense the 80s into a static block of time, there is an unchallenged agreement that the band were ironically mocking the yuppie subculture. In fact, yuppies did not exist in name or context until the middle of the decade. Heaven 17 were momentarily a portent of the future, although their suit wearing quickly became part of the post-new romantic scene-shifting and costume change dramas.

And then there was also Terry Hall of The Specials. He upped the ante for the 2 Tone craze for wearing close-fitting tonic suits by adopting an incredible oversized and exaggerated suit for the summer 1981 single ‘Ghost Town’. Terry then wore the suit for the final Specials UK gig as part of a carnival against racism at Leeds. I was there, travelling up on a bus organised by Derby Young Socialists, who offset the cheap bus fare by taking the opportunity to preach to the hapless passengers of glue-sniffers and young ska converts. Yeah, yeah, yeah… just get me to Leeds.

Here’s the backstory of that suit – it was apparently sourced by Roger Burton and Derby’s Dave Bonsall from a Nottingham fleamarket, tailored by a West Indian trader. It features in Roger’s autobiographical clothing collection Rebel Threads, a must buy for fans of clothes and music. In Roger’s words: “It looks like a cartoon mobster costume: damson gabardine with chalk pinstripes, squared shoulders, crazily exaggerated lapels”. Maybe, but Terry looks superb. However, it wasn’t a look that many people could pull off.

In fact, all suits were a hard look to pull off. If you had that sophistication, maybe a Bryan Ferry or Midge Ure louche appeal, then you could save up and get kitted out by one of the local boutiques such as Birdcage. There were always cool-as-a-cucumber punters occupying the box seats in Derby’s Blue Note or Nottingham’s Asylum, looking just so in an expensive suit. However, most ordinary subcultural explorers turned to the second-hand market to salvage original 50s suits with that all important but often elusive baggier cut. It was a strictly hit and miss affair. In Derby there were a couple of entrepreneurial post-punks who set up a market stall selling this gear, often re-tailored to save you the trouble of trying to create the right look.

I managed to get my father’s old suit, possibly the one he got married in, which was more classic 50s than the early 60s time of its use. Good old Dad. It had a baggy look, but the trousers were cut too short for my gangly legs. This added to their post-punk-meets-conceptual-art-gang attraction and could well pass for a very expensive Thom Browne incarnation in the modern era. We wore these suits to gigs and clubs in the early 80s, before the more defined post-punk uniforms of goth and other mid-80s subcultures came to dominate.

I distinctly remember wearing it to try to get in to the Blue Note club on a cold winter night in 1981 to see Manchester band A Certain Ratio who I had heard on John Peel playing their otherworldly wistful funk. I was hoping that my suit would bluff and bridge the three-year gap to the required 18 status – it didn’t, and I had to get the last bus home before the band had even took to the stage. I suspect I looked more like a child actor from Bugsy Malone than a member of Blue Rondo a la Turk. Those bouncers are probably still laughing.

– Ian Trowell