The arrival of punk rock in the provinces meant that existing venues for gigs had to suddenly accommodate a new music genre and all the hubbub that accompanied it. Punk had performative provocation and controversy in spades, which seemed to redouble its efforts when it landed in the East Midlands in 1976.

The Sex Pistols are normally the test case, and they don’t disappoint. Their gigging schedule which commenced in November 1975 goes up a gear in May 1976, when they progress from playing southern-based art colleges to bemused chicken-in-a-basket type venues in the ‘north’ (further up than Watford Gap services). They played a relatively unacknowledged gig at Nottingham’s Boat Club in late summer and were about to embark on their EMI-sanctioned ‘Anarchy in the UK’ tour for December. Frustratingly slightly before my time of gig-going, Day 2 of this was scheduled for Derby King’s Hall, an established venue that involved boarding over the regular swimming pool. A day before the tour a swear-a-thon on prime-time TV meant a moral panic was quickly whipped up. My dad was among the outraged.

Music folklore recalls them made to perform in front of Derby council dignitaries and functionaries before the punk package event could go ahead. There was talk of a satanic ritual as part of the act, never mind the potential of profuse swearing. The band declined – notwithstanding the roadies spending a deliberate elongated period of time building up the backline amps and kit to keep the consort waiting – and the Derby event never happened. The first of many cancellations on the tour. The farcical ceremony went down in history – more grist to their (bad) publicity mill. They had been pencilled in to play at Derby Cleopatras in September which fell through due to singer Rotten having a sore throat (though they may have been finessing the EMI deal at that moment, or a rumour of equal merit is the threat of a visit by a local chapter of the Hells Angels). They also played another low-key gig at Burton-upon-Trent in the last week of September – one for the punk collectors.

The Pistols never played Nottingham again but were the source of controversy when Virgin Records on King Street refused to desist from displaying their album Never Mind the Bollocks in the store window. This came to a head with a much-publicised court case evoking ancient English literature via a professor at the Uni and making the front page of the Evening Post on 24 November 1977. Store manager Chris Seale is photographed posing with Richard Branson, but the whole thing smacks of a typical publicity stunt which Virgin were prone to do with the band.

By late 1977 and through 1978 larger venues were putting on punk shows. King’s Hall in Derby relented and hosted many bands, whilst in Nottingham the Palais alternated between northern soul all-dayers and gigs by such as The Clash and Buzzcocks. There were also events at Malibu on Priory Island, once a cinema and briefly an indoor concrete skate park, and now demolished.

Smaller venues also thrived – the Boat Club regularly hosted punk and post-punk gigs, and the Sandpiper tucked away in the Lace Market area took on a new lease of life. Under the tutelage of Dave Nettleton (who ran early East Midlands punk gigs at Katies in Beeston), the venue succumbed to the new music scene in November 1977 with an opening night appearance by Buzzcocks, who seemed to tour non-stop. The Sandpiper saw some classic gigs through 1978 and 1979 as newer bands like Siouxsie and the Banshees and Adam and the Ants started to branch out into the provinces. Sadly, it was all just before my time, though the venue is remembered for being totally painted black to make it feel subterranean. As one punter recalls – it felt like walking into a Ghost Train. The club interior had the spatio-aesthetic disorienting vibe of a Doug Wheeler installation artwork where “the wall had forsaken its substances and turned into white space” – though in this case, black.

Over in Derby, commencing in spring 1979, was the Ajanta Theatre. Long since operating as a luxurious entertainment venue, it was at the time semi-derelict with a backroom bar dominated by a big tele that functioned as a pay-by-the-hour porn cinema. Other parts of the building were used as a laundry and a pickling plant by the local Indian community. So, perfect for challenging post-punk events such as a gig by The Fall attended by an audience totalling under ten, and a typical onslaught of noise and sound effects by Throbbing Gristle accompanied by an evening of fighting. This was where I cut my teeth in terms of experiencing live music, though the whole of a crazed crowd of weirdos and the ephemeral dwelling in a collapsing building gave it an added edge. You felt a natural inclination to slowly pick away at the depleted furnishings and fittings on every occasion, an entropic frenzy that resembled a dark mirror version of Gaston Bachelard’s Poetics of Space. Instead of celebrating the nuances and joy of inhabiting a home or building, there was predilection for undoing and un-dwelling.

Certain bands stood out for having memorable gigs in both Derby and Nottingham. Gothic-horror rockabilly outfit The Cramps played at the Ajanta in March 1979 and were cruising around the city beforehand in an open-top American car offering people a ‘ride’. A few months later they were performing at Rushcliffe Leisure Centre, supporting the Police who utilised a flashing police light on the gym floor as part of their set. Most of Trent Poly art school were in attendance.

And there was the Grey Topper at Jacksdale – possibly the strangest venue to grace the UK punk scene. A workingmen’s club in the mining area of North Notts with wallpaper louder than the bands. Lucky punters witnessed gigs by Ultravox, Adam and the Ants, Simple Minds, and many other punk mainstays.

As the 70s came to a close, new romantic sounds and an emergent post-punk-funk had a tendency to point away from the live venue and towards a dancefloor. Venues such as Rock City tried to bridge the gap, running their famous futurist night – though this usually centred around a live act of some sort. Mainstream nightclubs were no-go places – where being ‘weird’ singled you out for a one-sided fight, and you’d never hear any decent music outside of the more uninspiring top ten releases and some 70s leftover disco. There was a gap, a need, and so a bunch of new clubs sprung up to cater for this audience… myself included.

The music was eclectic but often had staple elements that pulled you into a lolloping, poppers-fuelled, immersive experience. Tracks stick in my memory where I was drawn to the dancefloor and lost sense of time and space: New Order’s ‘Everything’s Gone Green’ (1981) evoking a tunnel of bass and keyboard patterns, the Grace Jones classic ‘Pull Up to the Bumper’ (1981) with its louche and sparse funk and dub, the 12” mix of The The’s ‘Uncertain Smile’ (1982) with its endless skittering intro. All these tracks had big instrumental breakdowns that sent the crowd into raptures.

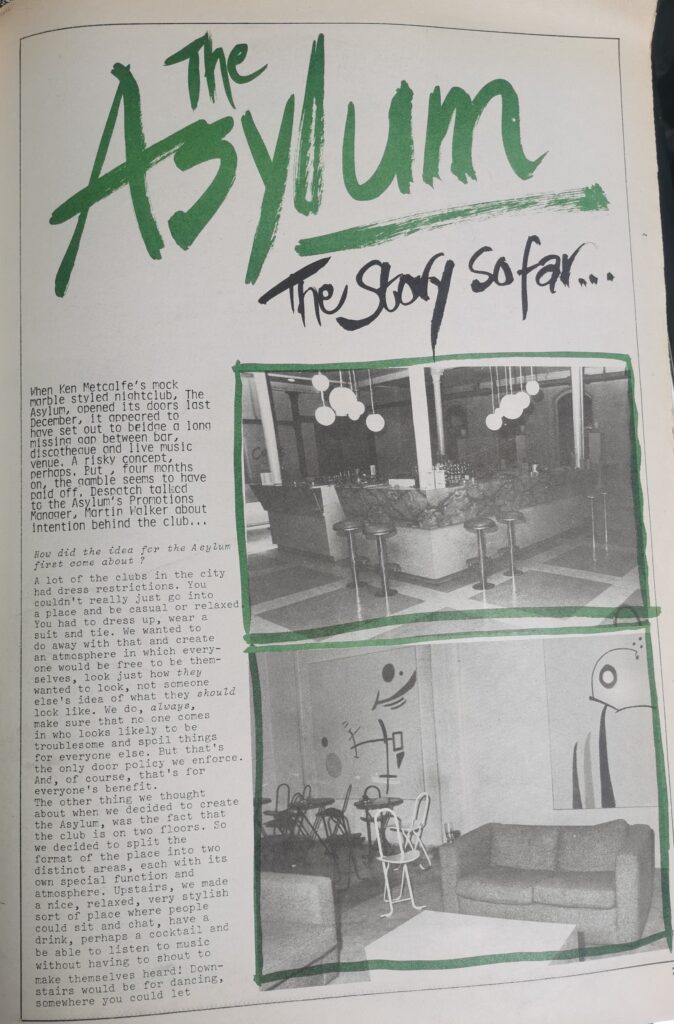

Bill Brewster writing the intro to Cherry Red’s triple CD of “militant funk and post-punk dancefloor” reminisces about his time in the formative post-punk moments inspired by watching A Certain Ratio in 1981. He mentions the boutique strongholds of the East Midlands such as The Garage and Blue Note. I’d also add the important venue Asylum, upgraded from Whispers in December 1982. I went to a few events there and it was my first experience of something approaching an all-night session. It closed around 5’o’clock, and we used to hang about in Broadmarsh bus station before getting the first Barton bus back to Spondon. We’d spend Sunday sleeping to be ready for school the next morning.

The Asylum was styled similarly to the Blue Note, a kind of deco modernism with sleek marble and stainless steel. The designer Ron Atkinson, co-founder of Despatch, was inevitably involved as he shaped the look and feel of East Midlands nightlife. The Blue Note took inspiration from Richard Gutman and Elliot Kaufman’s 1979 coffee table book American Diner. Fashion designers such as Olto were quick to take advantage, holding new collection promenades in there. These were dressy establishments, but not snooty or exclusive. Subcultural fashions flowed and crossed over, with many of the patrons supporting the vibrant local alternative fashion scene. The venue continued to hold small-scale gigs and live appearances. I recall in 1983 going to see Nicky Tesco (from pop-punk band The Members) teamed up with rapper/graffiti artist J. Walter Negro who combined his music with the live spraying of an impromptu backdrop.

More resilient in Nottingham folklore is the Garage, opened by Selectadisc owner Brian Selby in Autumn 1983. Nestled around the corner from the earlier Sandpiper, the Garage resided as the Ad-Lib club for many years, catering for dub and reggae music with the odd bit of live post-punk thrown in. As late as summer 1983 Robin Kerr of G-Force is promoting a new Ad-Lib night to dovetail with the scene around the fans of his fashion label. However, the revamp and rename to the Garage proved to be a masterstroke. The club played on its labyrinthine arrangement, allowing two spaces for music, various stairwell points, a diner of sorts, and an outdoor section. It was like an ecumenical church where all forms of subcultures came to happily co-exist.

The club was famous for groundbreaking gigs and club nights in equal measure. An array of performing bands came thick and fast with the local presence of two cutting edge ‘rock’ record labels: Digby Pearson’s Earache which pioneered a UK scene of skate-thrash and grindcore, and (not the clothing designer) Paul Smith’s Blast First and the earlier Doublevision video imprint which led the UK link up with New York noise and experimental music from the USA. On the club side of things, we had the regular DJs Martin Nesbitt and Graeme Park – the latter who would soon lead the field in cutting and pasting new-pop and electronic music with a perfect beat precision. Standing in the club around 1985, listening to him frantically switch between ABC and New Order, was a moment of revelation for me. It was no surprise that he co-founded one of the first UK-based house labels with Submission, formed with maverick John Crossley who was previously working with Nottingham’s C Cat Trance and the glorious splurge of output on Long Eaton’s Ron Johnson label.

It was this new strand of dance music, combining warehouse parties, early acid house, electro, and other strands that would emerge at the end of the 80s and define the next decade and beyond. The Garage, rebranded as Kool Kat, had new residents such as DIY soundsystem who had cut their teeth on the free party scene with its quasi-anarchist ethics. I recall coming across them at a freezing cold summer solstice party at the Derbyshire stone circle Arbor Low. Times were changing.

In Nottingham new innovators such as James Baillie were shaking things up and pushing things forward, putting on nights at Pieces (with David Keyte who was then working at Paul Smith and would go on to form Universal Works), Barracuda and Eden. The latter two venues also had DJ appearances by Michael Murphy who would go on to be part of Smashing, where the mood of escapism and dressing up linked back to the Vaughan and Franks fashion partnership. As the decade ticked over to the 90s, James launched Venus at The Club, a later incarnation of Whispers/Asylum but now catering for footballers and the like. It was a bold move which kickstarted the move for the 80s ‘townie’ disco strongholds to finally relent and cater for the new dance music scene.

– Ian Trowell