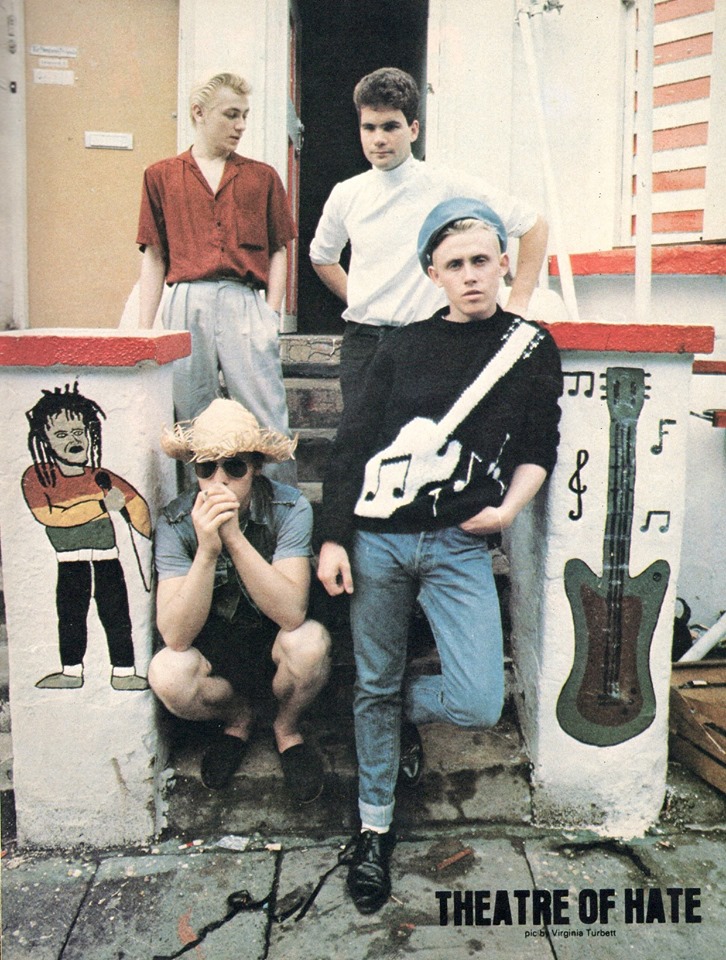

The collective identity and engagement of subcultures fractalized at pace during the decade changeover from the 70s to the 80s. If any band captured this moment of transitional energy it was Theatre of Hate. Founded by Kirk Brandon and combining elements from several already shifting punk bands, Theatre of Hate burst onto the post-punk landscape through the second half of 1980. They were fiercely independent, fiercely industrious and fiercely fierce. They had a rousing sound that had the driving thrust of punk, a haunted rockabilly twang, and a be-bop sax that breathlessly screeched in sonic synergy to the thundering guitars. Not to be underestimated, they also looked fantastic, taking a mix of military and utilitarian-punk clobber and combining it with the neo-rockabilly threads of labels like Johnsons. It felt like a new subculture in the postmodern vein, combining past elements with a future-forward panache.

They picked up the restless cast-offs of The Clash’s hardcore fanbase, who by the end of 1980 were not indicating any sense of fun or future. The Clash dressed well, working the vein of rockabilly-meets-punk with a nod to the new romantic spirit of dressing up – peg trousers and sleeveless shirts – but Theatre of Hate perfected this. They quickly attained a loyal following – bleached flat-tops, rockabilly shoes, heavy duty jackets and wonderful gear from places like Kensington Market.

The band, and their look, made it into a short feature for The Face in February 1981, with a chance to see Brandon’s iconic (and hard to come by) RAF cold weather MK3 jacket on display. It was a style marker, make no mistake. Brandon wears the jacket fastened up, with a scarf, as if ready to battle the elements and other more dystopian affronts. Later in 1981, new guitarist Billy Duffy, another style aficionado who worked at Johnsons, adopts the same jacket. This military look is typically fierce and edgy, as if awaiting the end of times. Theatre of Hate played it partly as style culture, also featuring in the new-romantic magazine New Sounds New Styles in April 1982, depicted encamped around a makeshift urban bonfire. Always on the edge, survival overriding celebration.

The followers of the band quickly adopted this hybrid look of smart punk-rockabilly clothing with the semi-utilitarian outer layers and accessories. It indicated a road-readiness, like a long-distance lorry driver crossed with a Blitz club regular. Army green kitbag, a rolled up sleeping bag and a stash of hitch-hiking signs were de rigueur. These were generally stowed behind the merchandise stall once you arrived at the gig. It was all very much a ritual or performance, a material extension of the subculture itself. Their fans were dedicated, almost obsessive and possessive like football fans, priding themselves by notching up a gig count, relaying tales of getting from one end of the country to the other by hitching through the night to fulfil dates at venues set hundreds of miles apart. Scrapes here, scuffles there. By any means necessary. The band even had a song – ‘Legion’ – which seemed to address this sense of belonging.

I managed to travel and catch Theatre of Hate live at a couple of events in 1981, including the third Futurama. I was still at school, in Derby, though to their credit the band did try and reach the parts that other bands couldn’t be bothered with (they never played Derby though). There’s a typically outlier gig in early June 1981 at Loughborough Town Hall, allegedly attended by Terry Hall and the members of Fun Boy Three to-be. The Specials were about to implode, and Hall was apparently observing the looks and sounds of Theatre of Hate – he would immediately start sporting an outgrown flat-top hairstyle.

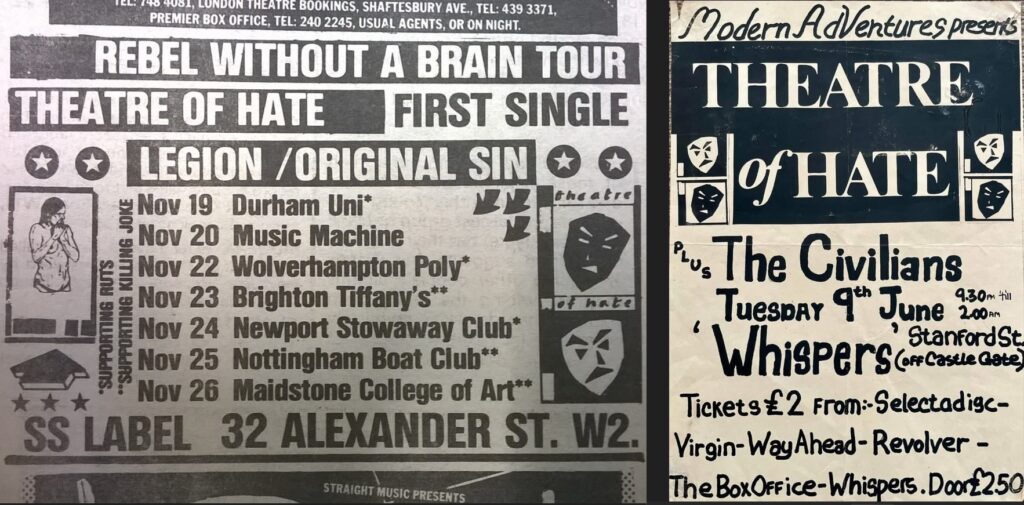

Brandon and the band put in a punishing regime of endless gigging, each barely demarcated tour merging into the next one. They performed at Nottingham Boat Club early in their career, switching back and forth between support slots for The Ruts and Killing Joke, pushing ever onwards. It was the latter who performed in the chaotic enclave of the Boat Club, and I can only imagine how much raw pent-up energy must have been unleashed that cold Tuesday night on the banks of the River Trent. They then added three Nottingham appearances through 1981: a slot at Rock City in March as part of the somewhat ill-matched ‘2002 Review’ ensemble headed up by Classix Nouveaux, a gig at the bespoke nightclub Whispers in June as part of their ‘March of the Conquistadors’ tour, and an October performance at the Clifton site of Trent Poly. As the band ducked in and out of the city, the local designers G-Force were building up their neo-rockabilly collection which chimed perfectly with the moment.

Following their non-stop schedule of gigging in 1981, the band started 1982 with releases of their debut album Westworld and a single cut ‘Do You Believe in the Westworld?’ that got enough chart traction to warrant a now legendary appearance on Top of the Pops. Airing on the evening of February 4 and compered by John Peel, Brandon unveils a new look with cut-off tasseled suede cowboy jacket paired with jeans, white socks and black buckle shoes. With an accompanying NME cover, their stock was growing.

The tour to accompany this album was also legendary, with the band assembling a rotating cast of support acts that presented the best in the niche post-punk work of tribal energies – UK Decay, Southern Death Cult, and The Meteors. Each band had a distinctive sound and look that somehow pulled together on the night. UK Decay sported a decadent new-romantic-meets-Seditionaries style, Southern Death Cult were labelled as the ‘Red Indian’ counterpoint to Theatre of Hate’s cowboys, and The Meteors were the fly in the ointment with their psychobilly culture that merged a 50s-schlock-horror-meets-skinhead mentality into the scene. The combinatorial rump was not yet goth in terms of that very prescriptive look to come, though the term Gothic (and bleak) was regularly applied to describe the grandiose gloominess of the lyrical themes and sounds of these bands, commencing in early 1981 with NME’s review of a Theatre of Hate gig. The shows were atmospheric and dramatic events, with an excessive use of spine-tingling intro-tapes drawing from classical music and film scores.

I was in attendance at the juggernaut of a gig at Leicester De Montfort Hall towards the end of the tour, where UK Decay and The Meteors were in support. On the plus side it was a Saturday trip that I was able to combine with clothes shopping. Leicester City, then in the Second Division, had beaten Queens Park Rangers 3-2 and so local spirits were high with that rival edge always present in football casual culture. The event was an electric atmosphere that was dogged by outbreaks of violence and a simmering tension.

Many gigs around this time tended to have a mixed bill of artists from different subcultural niches and nuances, all with their own fashion codes, and trouble was ever near. Anything that attracted a skinhead attachment or football casual crowd would be a ticking time-bomb, and skinheads and casuals would often turn up at gigs not scheduled for them with a sole aim of kicking off. A band like Theatre of Hate, with their following of ‘outsiders’, always generated hostility across both subcultural and geographical borders. That immortal question: “where you from mate?” as a precursor to a thump or headbutt.

Never being a natural fighter nor an exponent of macho culture, I was always wary of trouble at gigs and tended to be able to sniff it out and withdraw from the scene, even if it meant missing a bit of the gig. Quite often an evening spent watching a band like Theatre of Hate necessitated a heightened sense of awareness akin to a Special Forces operative on a mission in enemy territory. Your eyes were sharply focussed to spotting different haircuts and markers of clothing (particularly casuals who would be in attendance just for a scrap), and your ears finely attuned to sounds of raised voices, regional accents antagonistic to your own, chanting, goading, breaking glass, etc. On that evening in Leicester there were constant pockets of trouble breaking out during the performances and fierce running battles before and after.

It was, I guess, a test case for the time, before style culture and clubbing took a firm grip in the decade and everyone apparently suddenly got on with each other. The early 80s was peak subcultural diversity and demarcation, with an overlap of mods, grebs, skins, old punks, new punks, weirdos, football casuals, billies, soul-boys and many others up for a bit of territorial hostility and brinkmanship. On top of this there were the smoothies and townies who took offense to anything remotely different. These people sported a mix of some of the ska elements from 1979 – tassel loafers and sta-prest or tonik trousers – combined with the ski jumper look and cardigans in burgundy or lemon and grey. If you dressed remotely against the grain you attracted their opprobrium and apparently challenged the security of their manhood. Even wearing some pointed rockabilly shoes would single you out for scorn or worse. Outdoor socialising moments were spent forever on tenterhooks.

Theatre of Hate momentarily put it under the microscope. To intensify it further, their tours took in multiple resort places such as Cromer (West Runton Pavilion), Weston-Super-Mare and Colwyn Bay Pier. These venues are long gone, phantom places and buried moments. However, the gigs at seaside towns were often particularly violent, reinvoking the old seaside skirmishes of mods and rockers like a restless, dormant ghost army always ready to rise akin to the John Carpenter horror-film The Fog. There are harrowing stories of Southern Death Cult being barricaded in the changing room at Colwyn Bay as it was besieged by racist skinheads. Nearly half a century later, these memories still echo across the derelict coastlines like a barely surviving footprint of a Doc Martens sole in the sand.

– Ian Trowell