1. the youth club disco

Prior to all of this, in my early schooldays, there were ‘two tribes’ – to borrow a later phrase from Frankie – that dominated life in Spondon (and every other suburb). These would come in to focus at school discos, the youth club at the Methodist Church Hall next to the bypass, and larger events held at Celanese Club on Borrowash Road. The club was for the families of workers at the Celanese Factory, a large, chugging behemoth that sat on the southern edge of Spondon on the opposite side of the Derby-Nottingham railway line. My dad worked there as a miller. This is not to be confused with someone who presses grain to extract flour, such as Windy Miller in Camberwick Green. Windy in his proto-workwear such as styled by Old Town was holding down a look. My dad worked on a lathe, turning huge aluminium bobbins for the yarn and fabrics that Celanese traded in. He had dirty overalls, and a grime that clung to his skin and hair. He cycled home every day and used to feverishly wash and wash at the kitchen sink.

The youth club or school disco was very much an everyday or ordinary space. A chance to show off new clothes, to try a dance move, and maybe catch someone’s eye or get a kiss. I don’t want to add to the volume of writing that nostalgises on this formative and liminal space. Instead, I want to talk about these two tribes that were prominent around 1978, before punk went more mainstream and started to infiltrate the school playground.

Going to local youth club discos I remember there being a constant push and pull between kids into heavy rock (grebs) and kids into northern soul. Heavy metal had evolved through the 70s and was never really out of view. Northern soul flickered as an obsessive subculture for pill-popping devotees making weekend treks to their temples but had filtered down and regurgitated as a kind of subculture-lite of fashion for the playground and football terrace. Three-star jumpers and Birmingham bags. Northern soul originals are VERY fussy about their heritage and wouldn’t really class this late 70s degenerated version as part of the scene. But…

Both music scenes had distinctive fashion codes and dances – counterposed but still intricate, definitional and intertwined. The grebs in their festooned denim cut-offs gathered in two facing lines, hooking their thumbs into their belt loops, and ducking left then right whilst head-banging. It’s easy to lapse into a temporal blur and get them mixed up with the 1990 craze for line-dancing.

The northern soul fans with their high-waisted and multi-buttoned Birmingham bags trying to do that complex dance and footwork shuffle in their Clarks Polyveldt shoes that a handful of people make look effortless, and then – clap clap – hitting the floor with a bunch of trick moves in the instrumental breaks. Swallow-dives, floor spins, frenetic and corybantic sprawls on their backs and then jerking upright as if the dancefloor was suddenly channelling 1000 volts of electricity. Well, maybe two or three tried unsuccessfully, while the others stood and watched.

Each subculture lurked while the other had their say on the dancefloor. There was uneasy stand-off throughout the night. On one particular evening, in either a move towards some kind of subcultural democracy or an acknowledgement of the failure of a two-state solution, the DJ stopped the music and asked fans of each genre to stand to a particular side. The idea was to ascertain the dominant subculture and go forward with that. One of my earliest memories is being there at that moment and thinking “I don’t want to stand on either side…”. Punk was beckoning, the ill-fated opportunity to be shot by both sides.

2. the seaside

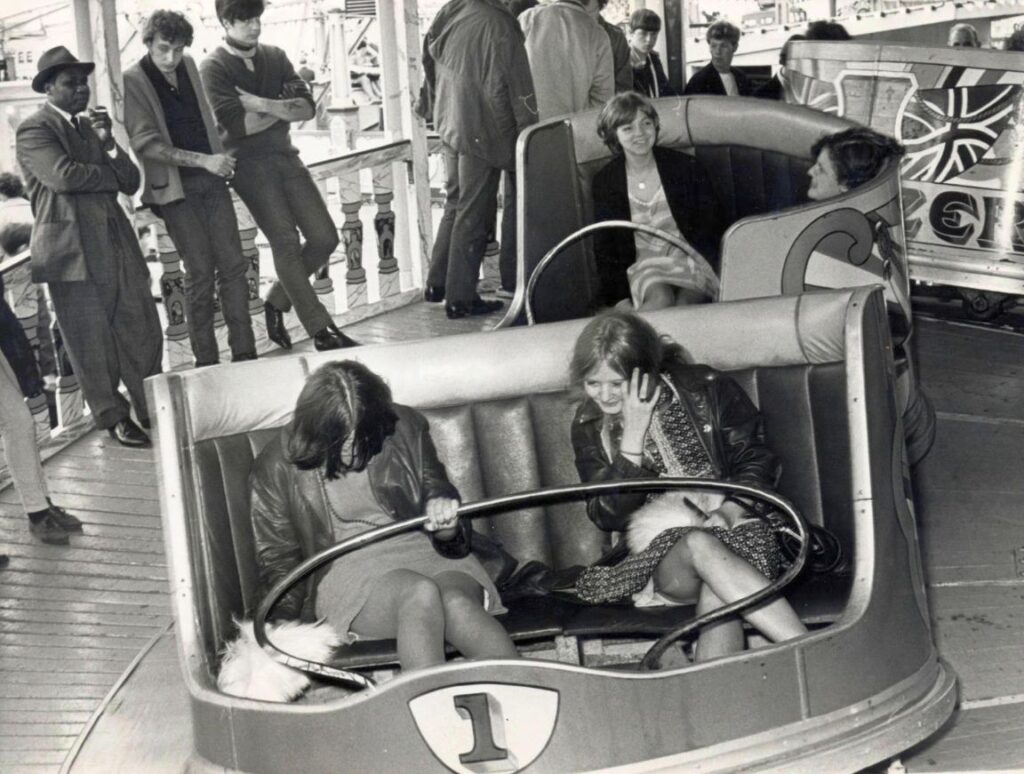

Like the school-age disco, the seaside figures in nostalgic fiction. A bawdy and liminal space where we can temporarily become someone else or act for the day on a kind of giant stage set with a semi-scripted drama. Subcultures have thrived at the seaside, with the tradition of mods and rockers slugging it out at more or less every major working-class seaside spot and the Blitz Club new romantics famously occupying the gentile sweeps of Bournemouth on the extended bank holiday weekends.

A subculture often requires a concept of territory to battle over, and the seaside fulfilled this role. Amidst the sociological analysis and creative depiction, there is nearly always a sense of a middle-class fear of grot and the ‘common’, akin to Mary Douglas’ much-quoted 1966 book Purity and Danger. Stanley Cohen’s seminal 1972 study of the seaside clashes between mods and rockers, Folk Devils and Moral Panics, is celebrated as a groundbreaking work that gave voice and vision to subcultural participation, but it has an undertow of contempt for the perceived popular crassness of the seaside. You can also feel this in O Dreamland, Lindsay Anderson’s short film from 1953 based upon a study of day-trippers to Margate.

The seaside of my childhood and adolescence was split between a ‘posh’ holiday in Bournemouth and a cheap and cheerful holiday in Ingoldmells, Skegness. In both instances, punk subcultures were glimpsed and infiltrated my receptive mind. A bolt of lightning struck during our annual trip to Bournemouth. For this we got an early coach from Long Eaton, midway between Derby and Nottingham, and travelled for the whole day to the south coast to stay in a boarding house. This departure was always a crack-of-dawn affair – I vividly remember the smell of my dad’s Brylcreem mixed with cigarette smoke as he got in a last desperate drag before the long journey. There followed a ritual scrum to get a seat, with my dad having an irrational fear of having to sit ‘over the wheels’ as this apparently made you sick.

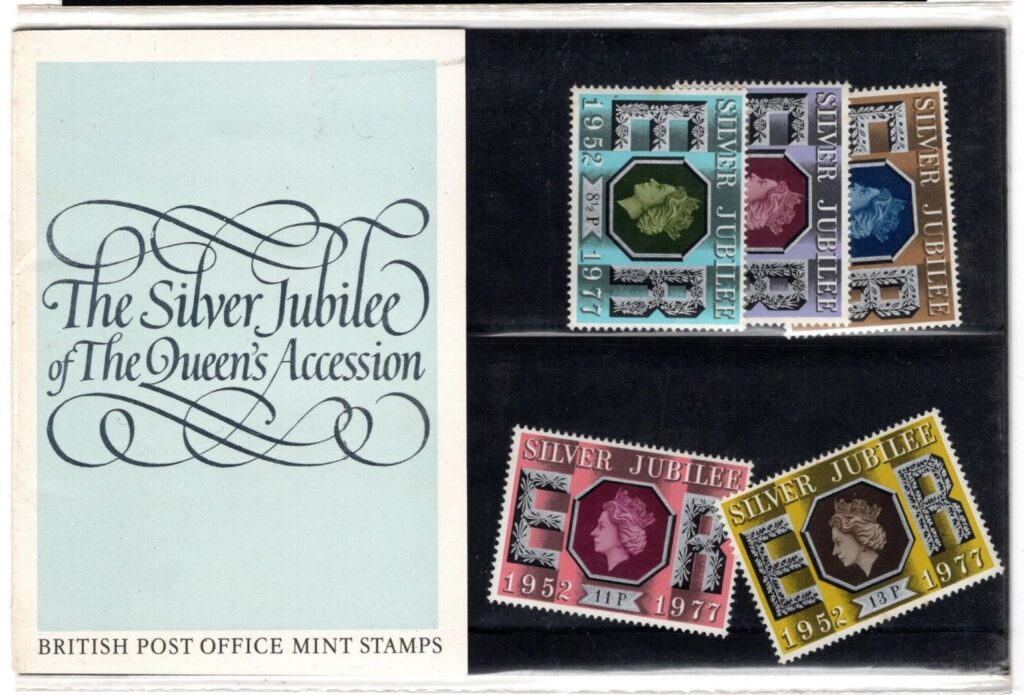

I have a crystal-clear recollection from walking on the promenade aged 11 with my dad, fetching mid-afternoon ice creams. It was 1977, timestamped through another hard-wired memory of buying a presentation pack of stamps celebrating the silver jubilee. It would be the time that punk-as-bogeyman had become well established in the minds of everyday people like my parents, doing battle with the jubilee. I spent most mornings with my brother racing up and down the pier pushing pennies into the arcade machines, whilst in the afternoons we went onto the beach as a family, swam in the sea, and walked the promenade for cups of tea and bottles of pop. My dad could relax, without seeing people from the factory, people from the estate, or anything to spoil his idea of bliss. Or so he thought.

On one afternoon we encountered a group of very dressy and arty London punks lolling and lounging on an incline in bondage clothes sporting dyed hair, horrifying the conservative Bournemouth populace. Flashbulb instances stick in my mind: bright red tartan, straps and zips, cans of beer fizzing away, loud belching, clumping teddy-boy brothel-creepers, boys-as-girls, girls-as-boys. My dad was equally appalled, mumbling about it for the remainder of the holiday, but I was entranced and it set a seed inside me.

The Lincolnshire resort of Ingoldmells is caravan site central, offering a cheap and cheerful break. We visited here for our other holiday, a counterpoint, accompanied by a rotation of grandmas and aunts. My dad is not someone who is posh, but he steadfastly refused to join us on the Ingoldmells holiday on the grounds of the place being so degraded. It served the industrial towns and cities of the East Midlands and South Yorkshire, with special trains such as the ‘Jolly Fisherman’ bringing in the excited masses. Subsequently, this meant that after dark there was often beer-fuelled massed fighting based upon an out of season continuation of the football rivalry of local towns and cities. Forest vs Derby vs Leicester vs Sheffield (who had two teams who would also fight amongst themselves).

The other phenomenon was that factories, such as the one my dad worked at, would have a shutdown week and everyone would take a holiday at the same time. Often, you would end up on a caravan site next door to someone you either worked alongside at the factory or lived next-door to. My dad was not anti-social, but this idea of a holiday (understandably) did not appeal to him.

I have some vague and more minor early punk memories from these holidays, as there were rows of seaside tat sellers in Ingoldmells where the caravan sites are clustered. At the tail-end of the 70s there was a profusion of punk and new wave badges that I spent my pocket money on. Predominantly oversized and often fixed upon a mirror base design, these badges shared space with an array of cheeky key-fobs, saucy postcards and cheap joke-shop novelties like pretend cigarettes, plastic fangs, miniature paper-wrapped exploding packages, blood capsules and fake dog turds. This type of tat (known in the trade as swag) was also common on the fairground, given away on ‘a prize every time’ stalls where you are offered the ubiquitous anything from the bottom shelf.

I distinctly remember buying Buzzcocks, Sex Pistols and The Damned badges – huge squared-off things. These would be pinned on my blazer in the times between lessons. I also strongly remember buying a badge with a rude Spoonerism declaring myself as not being a “pheasant plucker”, and a key-fob that had a cartoon of two pigs copulating underneath the phrase “makin’ bacon”. The smutty joke and act of animal copulation went over my head, but I liked the anthropomorphized smiles on the pigs’ faces.

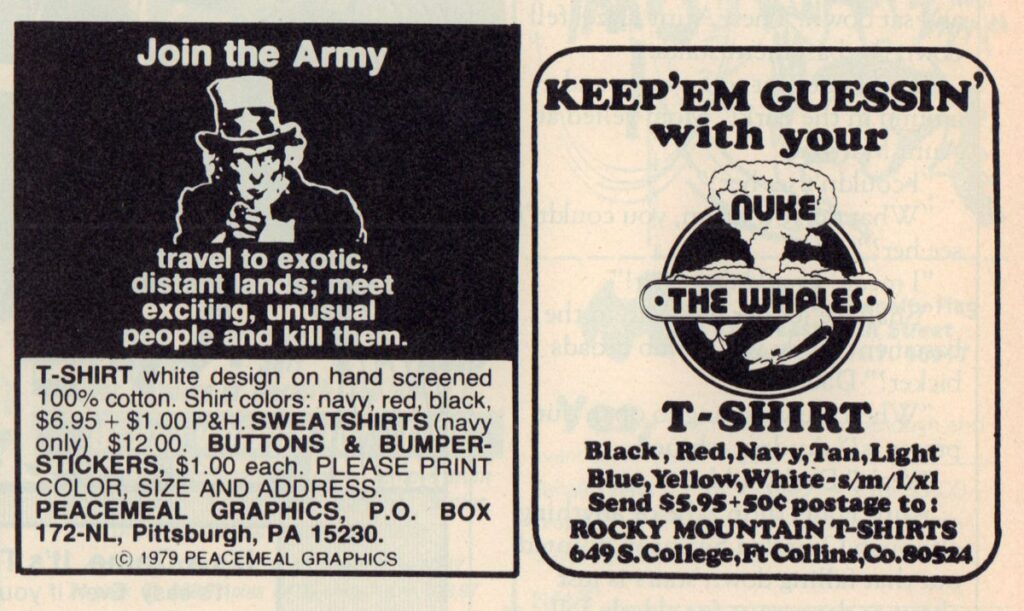

There was another key fob purchase that had a cartoon of a prostitute standing under the arc of a streetlight accompanied by the phrase “the customer always comes first”. As with the pigs, this went over my head, even more so, but I thought the cartoon woman looked good in a punk way with her sassy short skirt, stockings and spiked hair. This visual expression of humour, also available on a vast array of tee-shirt prints, leeched into the nascent punk subculture. Austere designers like Malcom McLaren would claim a situationist lineage of bawdy humour for his designs of hyper-sexualised Disney characters, but there was also this workaday humour that informed much of the provincial punk scenes – puns on joining the army to see beautiful places and kill people, graphics of a bespectacled and hapless turtle trying to mount a discarded helmet, the perennial “I’m with stupid”, etc. For a few years, this was part and parcel of the punk uniform.

3. the fairground

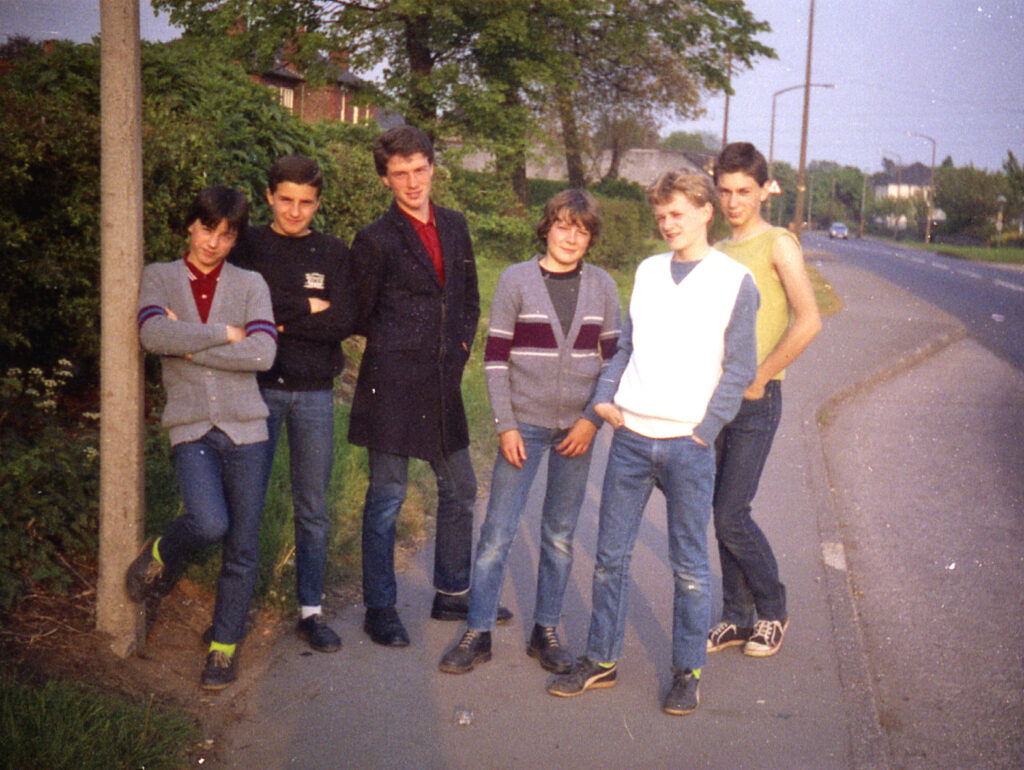

A photograph taken by me on Friday 14 May 1982, depicting a group of younger friends waiting for a bus to go to Long Eaton fair. A modern-day equivalent of August Sander’s farmers on the way to a dance. The fair was held both on West Park and the meadow near the swimming baths. In the fairground calendar it was a relatively large event with some showpeople from outside of the area bringing their rides. Towards the end of the decade the event was curtailed.

I’ve taken the 1982 group photograph with my cheap 110 camera. There must have been a good light on that balmy evening, as the handful of fairground photographs also came up with a striking quality of colour and reasonable amount of detail. The first thing that strikes me is the structural similarity to the hand drawn advertisement depicting subcultural tribes in an earlier essay. The arrangement of a line-up, with individual elements loosely interacting to create a flow, offers an uncanny congruence. The difference is obviously the lack of delineated subcultures. Instead, we have a blend of post-ska and casual, the early 80s colours of burgundy and grey on Fred Perry shirts and knitted ‘grandad’ cardigans, straight-leg and stretch jeans, luminous socks, tank-tops and cropped sleeves, and just one coat – a black Crombie. This is the everyday of steady-state subcultures: 2 Tone and new-pop, football codes.

British fairgrounds and music subcultures have an enduring relationship that reaches from early rock’n’roll through to more recent offshoots of the rave scene such as donk and mákina, niche genres that often acquire a moniker of ‘fairground music’. On top of this, fairgrounds are very much an everyday space of popular entertainment that also have that immediate heterotopic quality to become a magical elsewhere. The fairground is a unique sonic environment, residing like a series of densely packed overlapping soundsystems or discotheques with each large ride pumping out its music from cavernous speakers such that the beats blur and clash against each other as you navigate the enclosed space. Nottingham is, of course, famous for the Goose Fair – the pinnacle of them all.

From the 50s onwards the whole of the fairground became a space for absorbing and appreciating pop music, with impromptu events such as rock’n’roll dancing competitions being held on the Dodgems track before the fairground officially opened. Early music scenes were simply replayed on the fairground rides, as people stood around posing in their best subcultural get-up, trying to out-cool one another and attract the eye of the opposite sex.

You get the feeling of how the fairground and music mesh together through the opening frames of Ken Russell’s 1962 documentary for the BBC arts programme Monitor, with his film ‘Pop Goes the Easel’ focussing on the nascent pop art scene through the artists Peter Blake, Pauline Boty, Peter Phillips and Derek Boshier. A frisson of danger is portrayed in the 1960 film adaptation of Alan Sillitoe’s novel Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, with a coming to reckoning occurring at the nighttime Goose Fair.

In the bus stop photograph I’m absent… represented only by an elongated shadow. Even though, for me, 1982 was something of a fashion purchasing bonanza, there is a dearth of documentation. The shadow gives nothing away, but I’d have been dressed up in my best G-Force attire. My diary notes record that we got there, had a few rides (one of the group threw up after a ride on the Cobra), and then we were spotted and identified as ‘outsiders’ by a Long Eaton gang of grebs who arrived at the fair about an hour after us. Their nominal leader pointed me out, in my fancy clothes, as a particularly abhorrent invader. We had to make a swift group exit, doing a runner for the bus amidst a hail of hurled stones and insults. We were fast on our feet, a bus was conveniently arriving, and we got away unscathed. Bluff and bluster, subcultural psychodrama.

4. the seaside (again)

Sometimes you weren’t so lucky. Digging back into the diary notes; in the last week of July 1982 the fair returned to Long Eaton and I had an unchallenged evening there on the Friday night. The following day, Saturday 31 July, was an action-packed trip to Nottingham Boat Club to see Southern Death Cult. A real gathering of the tribes, spilling out onto the banks of the Trent to soak up the summer sun. But thankfully peaceful, numbed by booze, sunshine, good spirits and a sense of empowerment. On the Tuesday we had a day trip to Skegness, with mum and Aunty Linda, SDC’s tribal drums and hollering vocals still ringing in my ears. Then on Saturday 6 August three of us set out on an adventure, a holiday of sorts without parents.

We each purchased the Coast and Peaks Rover which allowed seven days rail travel across to Manchester and Sheffield (‘Peaks’) and onwards to Blackpool and the North Wales train line (‘Coast’). Child tickets, super cheap. The plan was to sleep rough and have a good time. We visited Blackpool Pleasure Beach, slept under the giant Astroglide at Southport Pleasureland, called in to see Wigan Casino before it was knocked down, and then headed to Rhyl.

We had stashed our sleeping bags in a bush by the bowling green off the prom and planned to sleep under the stars. All of us had packed lightly, but I’d got my best piece: a black and yellow knitted G-Force rockabilly cardigan twinned with baggy trousers. A bit of gel to maintain my flat top. We chanced a late-night bar with a small disco underneath doing a Pernod promotion. By a minor miracle we copped off with a bunch of girls who invited us to stay in their caravan. Wow, a first for me. Walking along the prom in the early hours we were suddenly accosted by a group of males, drunk and sore from not ‘pulling’. The words still rattle around to this day: “what are you, some kind of fucking rockabilly?”, then a fist straight into my face which knocked me down in one go. The British seaside.

– Ian Trowell