My first ‘real life’ encounter of an alternative clothing shop – outside of the cheap subcultural stalls on the Eagle Centre Market – would be in early 1981. It was more of a glimpse and a triggered intrigue. I was being slowly marched to the Children’s Hospital on the perimeter of Derby’s shopping nucleus, where large department stores, building societies and branded restaurants were replaced with solitary newsagents, junk shops and cheap cafes. I was due to have a potentially troublesome mole removed from my back, so my spirits were not high. Even having an afternoon off school did not counteract my sense of dread. Barely looking up from the pavement, I noticed the shop – Emporium – painted blue with a minimal interior and a small selection of clothes laid out such as I’d seen in The Face magazine. I went back there as soon as I could, penniless as usual, but wanting to explore and talk to the proprietor. By the time I had mustered enough cash to make a third visit and a purchase, the shop had gone. It was just an empty unit…

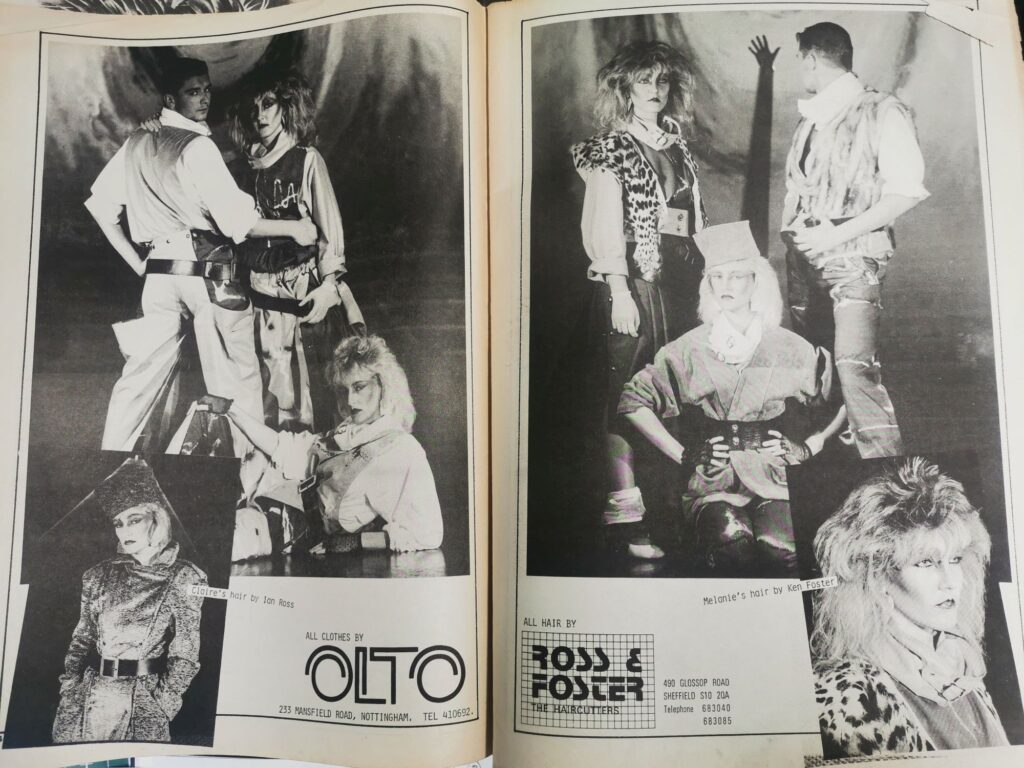

Emporium was a typical example. Alternative clothes shops often existed on the margins of the shopping spaces of towns and cities, relegated to the fuzzy and scuzzy areas where you had special or marginal interest retail spaces such as sex-shops, second-hand magazine shops, chaotically assembled vernacular model shops, and antiquated fusty-smelling pet shops that included the obligatory mynah bird that would produce expletives on demand. A great example in Nottingham would be Ollie and Tony Brack’s shop Olto, positioned at the top end of Mansfield Road as it climbs northwards out of the city centre before cresting over the hill to reveal the home of the Goose Fair (Forest Fields) threaded with numerous kerb-crawling red-light streets.

Olto originally opened in Hucknall of all places, taking over a vacant hairdresser shop on Watnall Road. You need a minute to digest that, when you consider the duo’s bizarre clothing that blended new romantic panache with rock star excess. After graduating at Trent alongside G-Force’s Robin Kerr and Brian Jakeman, Ollie and Tony built on their London connections as a couturier for various rock stars to bring this back to the East Midlands. He swears that there was a burgeoning clientele of cash-laden miners from Hucknall pit who liked nothing better than spending their hard-earned wages on avant-garde clothing. When you talk to Tony, still going strong with OneBC, it’s like the ‘yes/no’ game where he meticulously avoids using the word fashion to circumscribe his endeavours. He thrives on designing for the sake of artistic possibility and capability, driven by experimentation.

In 1981 Ollie and Tony shifted their operation to Nottingham, taking the small unit on Mansfield Road amidst the offcuts of retailing. Whereas at Hucknall they designed and manufactured on the premises, they now had a separate making space on Stoney Street with other creatives who were exploiting the cheap rents around the Lace Market area. On the top end of Mansfield Road there was the obligatory sex shop a few doors down (a “book exchange”), whilst over the road there was an Army and Navy surplus store that employed a local skinhead who would “sort things (or people) out for you” if that was needed.

Olto opened on Saturday 7 November 1981 and according to my diary I visited a few weeks later. I honestly don’t recall… but the photographs of the clothing in local newspapers such as Déspatch show a bold new romantic look, in the ballpark of Birmingham’s Kahn and Bell. I’d imagine that I would have been terrified to cross the threshold. Nottingham people fondly recall Olto’s efforts, with collections bordering on the conceptual. There was, apparently, a complete collection inspired by camping utilities – this being nearly 50 years before Craig Green’s much-lauded recent designs. Tony designed avant-garde window displays, that could be viewed from the upper deck of buses trundling up the hill.

Arnold born Karl Fox had spotted Olto in Hucknall, and being a fan of the new romantic and Blitz scene he quickly engaged the designers. He then oversaw the day-to-day operating of the shop on Mansfield Road as Ollie and Tony beavered away at the workshop. Karl was a budding explorer on the scene, seeking out clubs and clothing in other cities. A face about town.

Of course, there was a logic to this alternative clothing retail existing on the shabby margins, with the limiting factor of premium rent disbarring an independent designer or retailer a chance on the main thoroughfares of consumption. Contrary to popular belief about a drastic and totalising phase change that marked the opening of the decade, the societal changes under Margaret Thatcher’s rule were incremental. Her first term, after taking power from Labour in the ‘Winter of Discontent’ 1979 election, was more a case of laying the groundwork. Buttressed by an opportunistic conflict in the Falklands she secured a second term in 1983. This allowed her to settle an old score with the industry unions, glibly exemplified by the Miners’ Strike, before she achieved victory for a third time in June 1987. It would be in her third term that she intensified her sights on left wing councils and funding organisations that supported and promoted fringe activities in the arts.

Fashion design and retail through the 80s is a curious subject. The Conservative historian view (Dominic Sandbrook, Dylan Jones) has the new romantic scene of small-scale designers and club-runners as being an incubative forerunner of the wider materialism and individualism that came to stand for the decade (yuppies, etc). As recent work by historian Matthew Worley has implied, it was not so clearly defined. The period of the early 80s, within Thatcher’s first and second terms, saw a cluster of like-minded individuals exploiting cheap rents, concessions, government grants and opportunities to eke out both a living and a preferred lifestyle on their own terms. However, it was generally survival over entrepreneurship. The textile design partnership Katsu – formed by Trent Poly graduates Kath Townsend and Sue Watton – is a case in point, with the pair moving between various production spaces shared with other creatives (including Sharespace, King John’s Chambers and The Works, Carrington Street) and topping up their Enterprise Allowance subsistence with bar work at pubs or running the café at The Garage nightclub.

Designers aided their customers by keeping things as affordable as possible, and customers showed loyalty to designers. A 1985 interview with G-Force co-founder Robin Kerr in the newspaper Relay emphasises this, with Robin talking about how it is important to keep his prices fair for his local customers who in turn support his retail efforts. Club nights and gigs saw the whole social ensemble mix and chat. It was a layered yet un-tiered network of supportive creatives, spanning to obscure individuals such as Andrew ‘Baby’ Woodhead who apparently would fashion you a bespoke suit from his flat in the Victoria Centre!

Let’s return to the idea of these shops being out of the way or semi-hidden, of being something of an adventure to encounter and engage. Their understanding and appreciation from the viewpoint of the customer is more complex. These shops didn’t work solely as an instance of retail, they also functioned as an enclave of subcultural ‘being and doing’. A great example is the short-lived shop ID in Derby. This was established by local activist Dave Bonsall as a punk shop in 1978, though it stocked a more progressive post-punk range of clothing. More so, it served as a meeting space for people on the scene, as a refuge from loutish ‘teds’ or casuals, and offered a rehearsal space in the rear where various Derby punk and post-punk bands were germinated.

Seeking out alternative clothes wasn’t entirely a means to an end, and it extended beyond the more recent joys of materialistic clothing shopping where people chase the thrill of just buying something new to post unboxing footage on social media channels. As you can imagine, setting out to find these shops, and entering them, became something of an adventure or rite of passage. It needed planning and tactics – a ritual that was a part of the subculture – with the out of the way locations adding to the experience. Cultural geographers would call this distribution a cartography of taste, but the French philosopher Michel Foucault coined a more apt concept with the idea of the heterotopic space.

Foucault was part of the post-war Continental philosophy movement (centred on France) in which dominant modes of language and thought were challenged and uprooted. Neologisms for ungraspable concepts came thick and fast, like bullets from a gun, but Foucault’s heterotopia was very much something that could be felt and applied. It made sense, concerning the feeling attached to a space such that this seemed unusual, discomfiting or disconcerting, in turn making the space itself appear topologically impossible or out of joint. Sudden switches in mood were evoked in places like a cemetery or a travelling fairground on a patch of land, sometimes a more abstract ‘space’ such as your own voice talking into a telephone and moving on to the recipient, or the generated region ‘behind’ a mirror. Often this was a topological incongruity – two different spaces (as defined by mood) occupying the same space, or a switch between spaces without a discernible border or egress. The map as a sense-making tool becomes derailed. Alternative clothing shops had a strong heterotopic aura, they seemed to exist in a different world that was encountered in the immediate vicinity as opposed to when crossing the threshold.

Returning to the example from Derby: Dave Bonsall’s initial shop Society Styles (said to resemble a front room, much like McLaren and Westwood’s first incarnation of 430 King’s Road) was on the fringe retail area around Abbey Street amidst slum rentals, taxi offices and shut-down premises, operating in the early 70s. His follow-up shop ID was an archetypical punk shop, sat in the middle of a crumbling part of the city that was awaiting development, the shop embedded into a dilapidated hotel structure that felt like something left over from the war (which it was). It had minimal exterior, no signage or curated window display, and had iron bars covering the windows. These stayed on even if the shop was open, in the same way that many punk clothing shops had permanently fixed rectilinear grilles. As with the famous punk shop Sex/Seditionaries in London, it was intimidating to venture through the subcultural checkpoint into a different world.

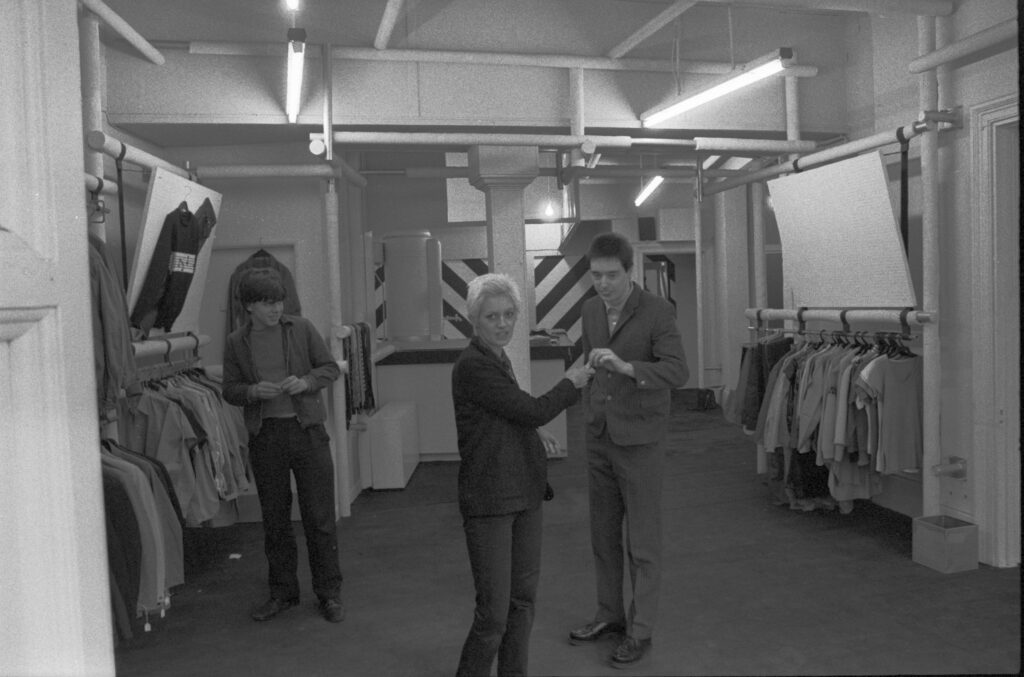

In Nottingham, G-Force was pre-dated by the ‘shop’ Jakeman and Kerr, hidden away on Bottle Street and in operation around 1978. It served as both a production space and a retail point on Saturdays. Brian and Robin deliberately made the shop appear unlike a shop, with no branding apart from the name Jakeman and Kerr on the outside door. This led to a second door which was also stencilled with the duo’s name. The intent was to make it feel like a firm of solicitors. But it wasn’t. Another example of Foucault’s heterotopia.

For their rebrand into G-Force in 1979 the pair initially painted the external of the new shop on Goose Gate in grey paint. Not just the woodwork, but the windows. They left a small letterbox look-in point. It created a heightening of tension, bordering on intimidation, as well as a sense of exclusivity into an underground sect.

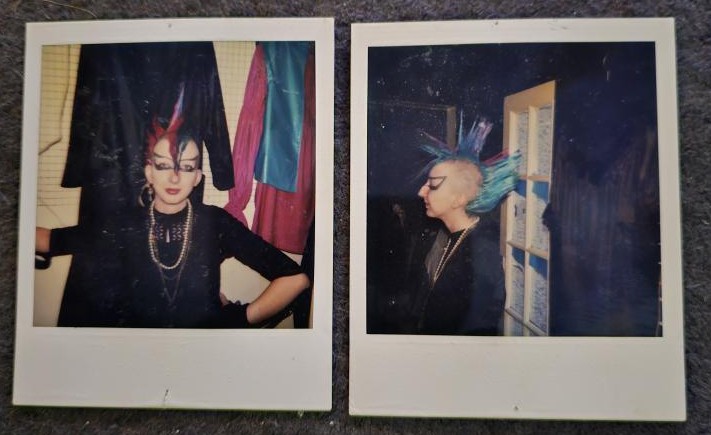

A final component in this intricate dance of intimidation would often be a shop worker who had an aura and appearance of unapproachability. The famous example is Jordan at 430 King’s Road, but Olto had their own Jordan at their tiny Hucknall shop. Step forward Christine, with her towering prototype Mohican in multiple colours and Adam and the Ants era Jordan style abstract make-up. Weird shops, weird places, confusing décor, frightening staff members – for many reasons, these punk and post-punk shopping excursions would stay with you for a long time.

– Ian Trowell