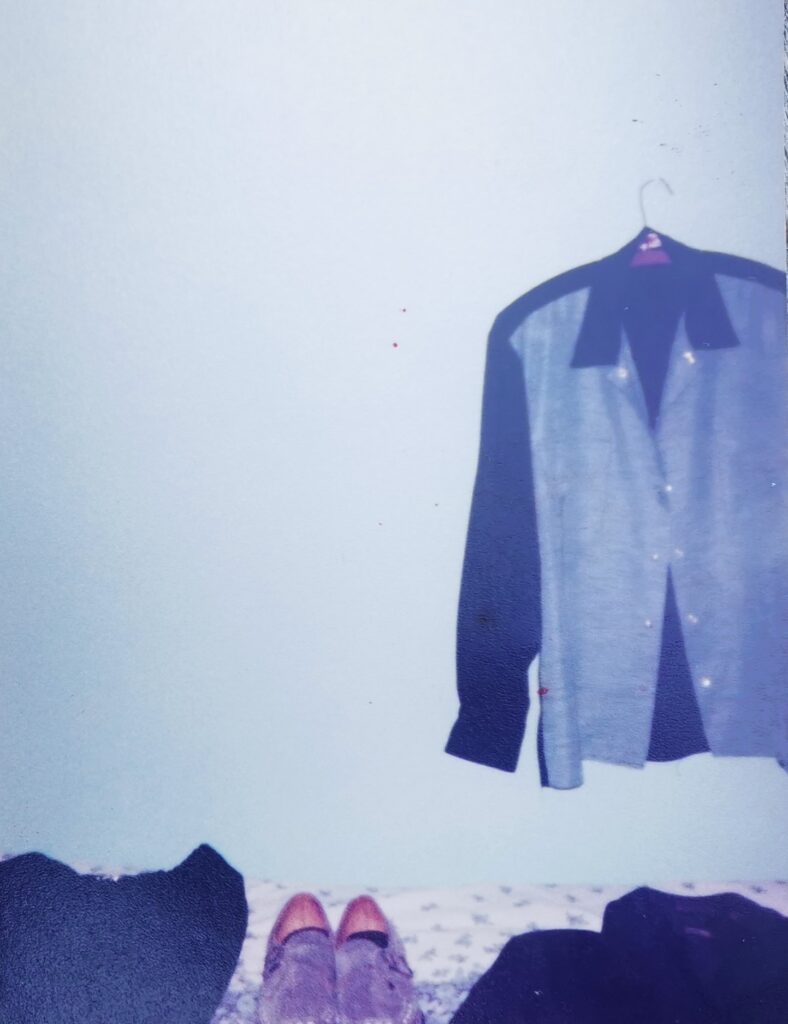

Two photographs. January 1982, an arrangement of clothes on my bed and a pair of new shoes on the living room carpet. I know these are BRAND new shoes because I wasn’t allowed to wear shoes in the living room. Punishable by death. These are the first photographs I took of my clothes. Clearly an important moment, a celebration, and a memento of an ‘upgrading’ towards how I went about constructing myself in a subcultural fashion. Farewell to the Eagle Centre punk days.

It is also very much an ‘everyday’ or ordinary arrangement, an approach to celebrating our subcultural and fashion heritage taken up by recent publications such as Sam Knee’s The Bag I’m In (2015) and Nina Manandhar’s What We Wore (2014). A capturing of the energy and exhilaration of the moment, of stepping out into a brave new world. Of taking a risk against the beer-boys and football casuals.

The two photographs are, on first glance, unremarkable and overlookable. Bear with me as we apply some subcultural forensics. There are numerous ways to approach these photographs, drawing from biographical material culture. I’d like to think about the ‘coming to be’ of the photographs, the setting of the photographs, and the subject of the photographs.

In early 1980 I purchased a cheap 110 camera. This is the popular style that had film with a double spool cartridge that you clicked into the back as film passed from one chamber to the other. It meant that it was foolproof, but the quality of pictures was dubious, as the camera never let in much light making pictures murky and grainy. I was normally meticulous with retaining and ordering things, but I don’t have any surviving negatives from 1980 or 1981. There are photographs, but maybe these were taken by my dad – he wasn’t a camera buff and so also had a cheap camera.

Photographs of the back garden and the dogs were accumulated – sunny moments without grand context or sense of occasion – just youthful days passing. Visible blooms of punkishness such as day-glo socks, band tee-shirts and peg trousers can be glimpsed. Other things come into view. A recalled photograph of Grandad Fred in which he twists and peers into the viewfinder with 70% of the photograph blocked out as I had my finger over the lens. The 110 camera had a separate viewfinder and lens so there was the double jeopardy of both a parallax error and the danger of you putting your finger over the lens without realising it. Grandad Fred had one eye, after an accident in the war, and he peers into the fraction of the aperture unobscured by my digit as if mastering the hindrance of the cheap equipment in a silent Zen manner. In some ways with his one eye and empty socket he appears like the dysfunctional camera with a single lens and broken viewfinder, his own parallax error to account for. Grandad always spent Sunday afternoons camped on our settee watching the tele. He never talked about the war but spent his day glued to the screen watching The World at Waror similarly themed films.

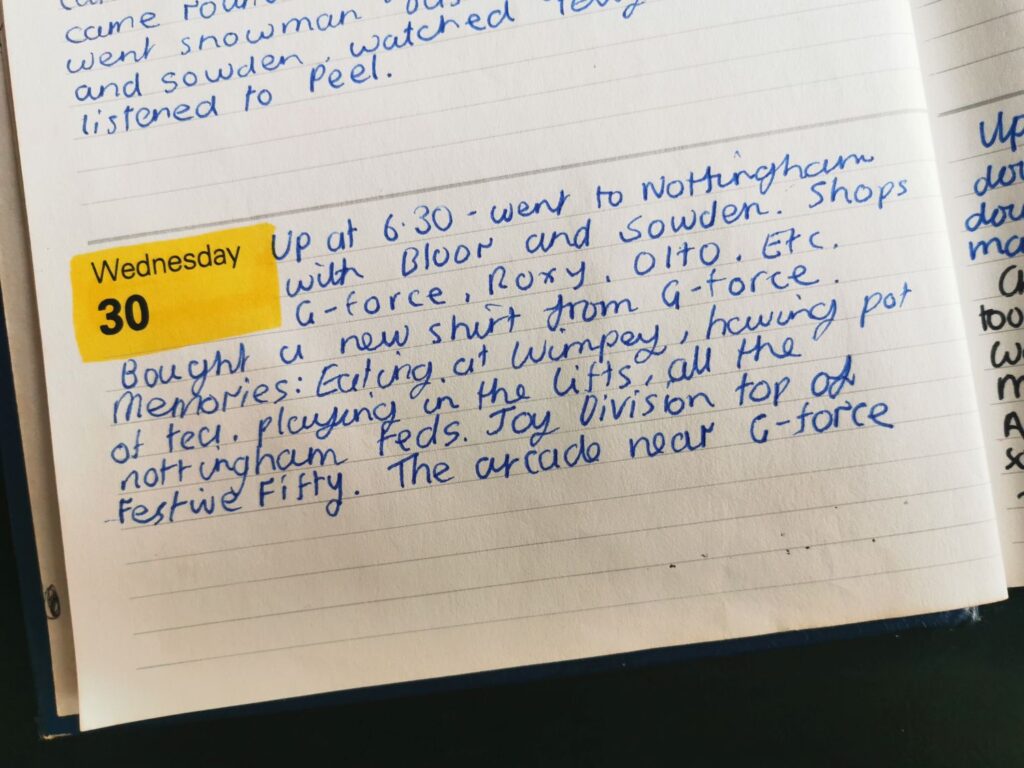

These two photographs are also without negatives. I have felt-tipped the date on the back – Jan 82 – and that seems right as I purchased my first G-Force clothes around that time. I have surviving diaries from 1982 onwards documenting my spending sprees, but some of these garments were bought before the diaries commenced. The shoes however, were purchased on Saturday 30 January from the Nottingham G-Force shop. A seismic moment, a rite of passage – the investment in the correct footwear. I’m guessing the photograph would have been taken that evening or the day after – a Sunday, the last day of the month.

The quality and composition of the photographs is typically poor, possibly over-excited. The bedroom photograph is off target, and I manage to not quite get the entirety of any individual thing! The shoes photograph is slightly better – landscape format and locked on to the subject. The garish carpet somewhat overwhelms things. But it was always clean.

The bedroom setting reveals a private space. The site of the ritual of getting ready to go out, of experimenting with different looks. I was lucky enough to have a bedroom to myself. Furthermore, being the older of two brothers I wasn’t designated the box bedroom. At this point in time it’s a plain woodchip wallpaper, painted in light blue, but lost in the electric blue of the shirt and grey blue of the shoes. I’d soon decorate the bedroom to my own choice, but that’s another story. My parents still live in this house, and the bedroom resides as ‘my’ bedroom, though used by my kids and now grandkids. I think it might still be the same bed. Sadly, the G-Force clothes are long gone, unceremoniously thrown out by my mum when I left for Sheffield in autumn 1984 as a semi-goth. It’s not something I like to dwell on, the throwing away or the goth-ness.

The living room photograph was taken at one of the ends of the room, as that is where the radiators were (and still are). You can just make out the waffles of the radiator in the bleached-out background. As mentioned, the carpet tends to destroy the discernibility of anything else – my new shoes and baggy old-man trousers. The living room wasn’t my private space, so posing photographs like this are rare. I’m pretty sure my parents weren’t around when this photograph was taken, and I have no idea who I asked to take it. My brother, a friend, a girlfriend from a (short-lived) relationship who might be thinking “what the hell have I signed up for with this boy who wants his shoes photographing”.

Going back to the bedroom photograph we can clearly identify the subject. Clothes; new clothes. There’s nothing else in there – no surprise punctum to be spotted as the eye relaxes and searches, as the theorist Roland Barthes might say. Not a wrinkle in the bedsheet or some such thing that hints at a harrowing story. The shirt sticks in my memory as it was the first shirt purchase (of many) by the Nottingham designer G-Force. I’d seen the label featured in The Face for summer 1981, and was hooked in by the neo-rockabilly look that the magazine promoted with bands like The Polecats and other shops/designers in faraway London like Johnsons, Rock-a-Cha and Marvelette. I can recall every detail – the lustrous blue fabric with horizontal fleck that formed the front of the shirt, the red and black logo label, the pearl press-stud buttons and cuffs, the fresh fabric smell. There’s a pair of G-Force shoes, a jacket of some sort, and some peg trousers. The shoes and trousers repeat in the second photograph. These things meant so much to me. I cannot emphasise that enough.

G-Force created clothes similar to Johnsons of London, but at more affordable prices. As co-founder Robin Kerr says, there was a shared outlook and a rediscovering of 50s designs and ‘deadstock’ fabrics. Shoes were licensed from exclusive Northampton manufacturers to a number of clothing companies – G-Force included. I went crazy for this stuff, and it became my singular look through 1982 and 1983.

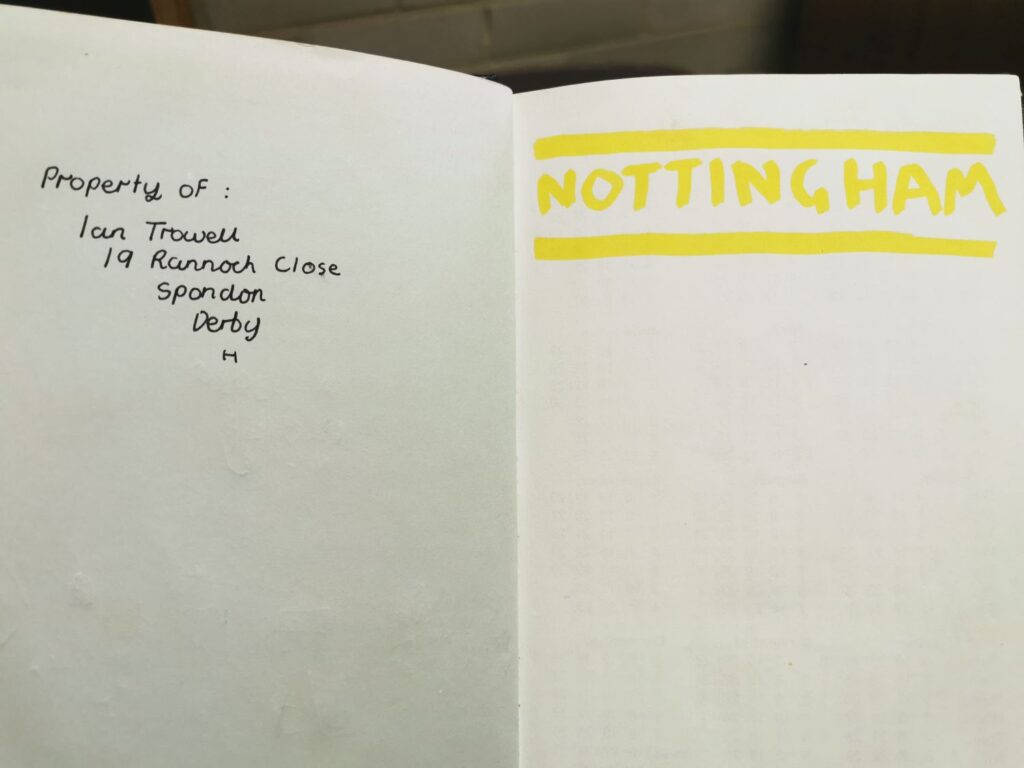

My 1982 diary opens with a yellow capitalised headline filling a blank page, simply declaring ‘NOTTINGHAM’. There’s no immediate context or explanation, just a joyous statement of intent, a switch of allegiance from the plastic punk haunts of Derby. The first week has an overlap to the last dates of 1981, and a cross-reference to the yellow highlight (survived for over 40 years) provides a clue. There is the record of the shirt purchase – a mention of G-Force, Roxy (Threads) and Olto, a burger at Wimpey (sic), an abundance of teds, and the attraction of amusement arcades (I’m still a kid at this point).

Throughout 1982 I am plotting and planning to save for clothes, drawing up lists of what I wanted, incremental savings schemes scrimping pocket money and marking off the weeks until I could make a purchase. The 2023 book by Mark O’Flaherty – Narrative Thread – looks at people who collect and cherish subcultural and avant-garde clothing, with O’Flaherty himself recalling how he fixated on and similarly scrimped and sacrificed towards designer garments.

My diary became a repository for lists and drawings relating to what I desired. As purchases were made these were joined by lists of what I had, and ideas for combinations of clothes, or strategic plans of what to wear for gigs and events. I made notes on well-dressed people I’d seen at gigs or around town.

G-Force caught that stylish hybrid of punk and rockabilly pioneered by the Clash and later adopted by overt rockabilly bands like The Polecats and more edgy punk-noir bands like Theatre of Hate. Chunky knits with skulls and music notes, sleeveless shirts with pearl stud fasteners, boxy suit jackets in lime green and pink, black shirts with decorated shoulder sections, jumpers and cardigans with leather and suede sections and stud patterns. This was briefly my universe.

As much as it was a singular look, it was also drawn from numerous subcultural currents. Pink was everywhere in this clothing, part of the new wave imagery at the end of the 70s. The abstract artist Mary Heilmann created a series of pink on black images such as Save the Last Dance for Me (1979), inspired by the feeling of new wave album sleeves such as Tuxedomoon, and the clothing of G-Force embodied this visual pattern. And of course, in 1982, if your different clothes didn’t attract negative attention then wearing pink certainly would.

Purchasing this branded clothing required hunting around in esoteric shops, a practice that thrilled me to the core – it felt like a phase change from the previous arrangements of salvaged clothing or trips to the ubiquitous Eagle Centre Market to get reproduction subcultural clothing. Nottingham had a popular punk shop in the middle of Hockley, proudly anachronistic, selling bands tee-shirts and studded belts. It was a few doors down from G-Force, and I always read it as a watermark of where I had come from.

Returning to photography, my earliest surviving negatives are from an April 1982 trip to Leicester to visit the small clothing shop Jive and the G-Force shoe shop in the multi-storey and decorative Silver Arcade. I knew about the shop, an expansion from Nottingham, because of an advertisement in i-D. Silver Arcade was a wonderful space though Leicester was an edgy city with a large skinhead presence. You had to be on your guard all the time. I know the city has recently queried and unpicked its subcultural legacy, with exhibitions and the wonderful book Perfect Binding (2019) by William English.

I was parsimonious with my photograph taking, but the excitement of encountering the G-Force shop triggered three photographs: a view from the opposite balcony over the interior void of the Silver Arcade, an overhead view of the shoes in the window display taken through the glass (evidently the shop was closed), and a later image when I returned to find the shop open and took a photograph of the shoes displayed on a white vertical peg-board.

According to my diary I never made a purchase, so heaven knows what the shop worker thought of me, most likely quizzing him to the point of tedium on different styles of shoes and asking if he knew which bands wore which styles. I noted in my diary that the staff member was called Cliff. I felt I needed to pull towards these people. Decades later I learnt of the playful interpretation in David Hockney’s painting We Two Boys Together Clinging (1961), and its reference to Cliff Richard.

The close-up overhead photograph of the shoes is scintillating, even with my finger partially obscuring the view. I regard this fleshy infraction as a tactile index of the sheer excitement of the moment which a photograph in itself cannot capture. Four models are evident in the unobscured region, all with a pointed toe and visible G-Force logo in gold script: a buckle fastening black shoe with a diamond pattern of nine studs, a similar design with leopard spot upper, a lace fastening animal print upper, and a lace fastening blue suede shoes.

The power of these shoes was difficult to describe – a similar feeling attributed to Malcolm McLaren by Paul Gorman in his 2006 book The Look. McLaren’s purchase of blue suede shoes from Mr Freedom at the end of the 60s is said to provoke a “seismic effect”. Hence my odd photograph. It’s my equivalent of Warhol’s 1981 image Diamond Dust Shoes. Warhol’s picture is cropped on all sides to connote a limitless terrain of shoe fetishism, but it shares a similarity with my photograph such that all the labels of branding are artfully displayed. In one of his typical grand and ironic gestures, Warhol sprinkles and bonds diamond dust into the picture to buttress the picture’s role as moving from a record or representation to a desirable thing-in-itself measured purely by money. G-Force shoes didn’t need that.

– Ian Trowell