In the late 70s and cusp of the 80s music newspapers such as NME and Sounds were a way in for a teenager looking to become part of a subculture such as punk rock. Particularly for someone living out in the provinces. Record shops and specialist clothing shops existed but could feel off-putting to an exploring novice. In terms of the music itself, John Peel’s late-night Radio One show proved invaluable. Gigs were a constant fixture but often had an age barrier combined with what felt like at times the intimidating nature of an aggressively conspicuous and sometimes conspicuously aggressive scene such as punk. In contrast, music newspapers could be imbibed in a private, personal space, or discussed amongst close friends with shared intents, a laboratory of taste and image construction. Trialist tribalism perfected in the bedroom and rolled out in the school playground.

The obvious lines of connection were record reviews, interviews with bands, live gig reviews, and learning to trust certain journalists who you felt spoke for your tastes. That became increasingly difficult as music journalists adopted various postmodernist and post-structuralist poses, locked into a private battle that made little sense to readers such as me who were midway through a secondary school education that had an endpoint in either a factory or on supermarket checkout.

Aside from developing and finessing a taste in music, the newspaper was also a space to facilitate the acquiring of a correct image or fashion linked to a subculture. This was primarily afforded through photographs of bands, occasional photographs of fans, and advertisements for record releases based around visual material. Programmes like Top of the Pops also helped. These visual sources gave you a basic set of ground rules of how a punk (or post-punk, or punky-rockabilly, or rude boy) looked, or you could mimic (partially or wholly) a particular musician who stood out in their scene. However, over-egging this copycat gesture often brought a certain amount of peer group opprobrium. The onset of glossy magazines that catered for punk and post-punk music and style, touched on by Smash Hits but pioneered by The Face and i-D, would not arrive until 1980.

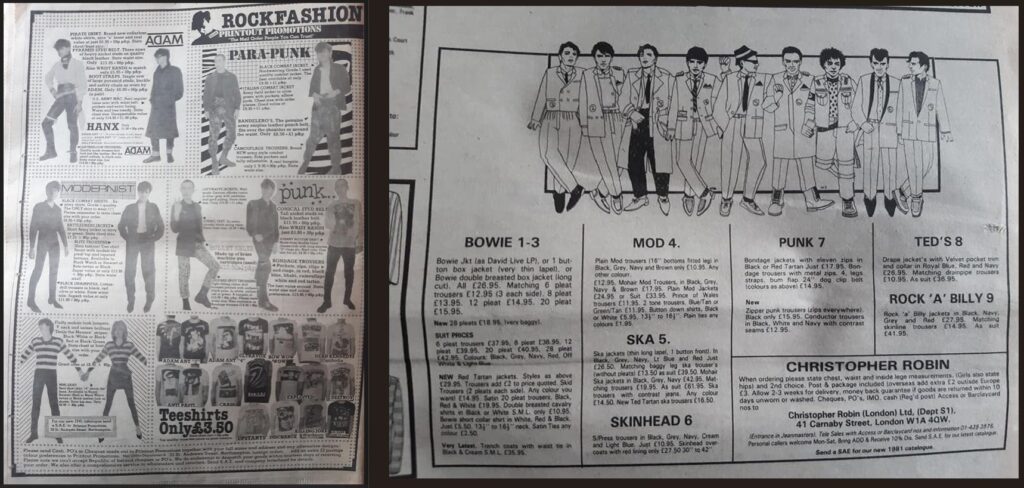

This need for both learning how to look, and acquiring that look, was quickly exploited by several mail order advertisements in the back pages of music newspapers, set out with crude sketches or blotchy contrast photographs depicting people with the requisite look. The small advertisements offered punk clothing as either part of a smorgasbord of subcultural themes, a punk only arrangement, or occasionally a range of clothing dedicated to a particular band – such as a regular advertisement for “Clash Gear”. Punk goods included bondage designs, bandmaster trousers, adopted military jackets and trousers died black with added studs and zips, and drainpipe trousers in either tartan or fluorescent animal print. It was more stereotype than archetype, with the advertisers often back-of-a-unit fly-by-night operators. The intention was obviously to lure in punks, mods and skins from the provinces. People like me.

These advertisements often had the equivalent of ‘rogues’ gallery’ of subcultural characters, with figures lined up in a fantasy cockney knees-up configuration, a subcultural menagerie. Like Miss World contestants from another dimension, each figure sports a badge with their allocated number. Starting on the immediate left of this motley crew we are presented with the three Bowie clones and their outfits – two based on suits and one sporting a trench coat as a “very latest” offer. The jackets are split between a one-button boxy cut and a double-breasted design, though the descriptions of the lengths do not match the pictures. Meanwhile, trousers are demarcated by the number of pleats in the trousers (up to 28 as “very baggy”), with a note for new red tartan jackets and “Skid trousers”.

The three Bowie boys are followed by a phylogenetic subcultural trio akin to stratified layers of fossilised styling: a mod, a ska fan and a skinhead figure. It is approximately chronological but these subcultures loop back with ska informing skinhead informing ska once again to give rise to second (or third) incarnation of skinhead. The clothing description for the mod figure bears a simple wording of “mod trousers” and “plain mod jackets”, requiring some subcultural faith on behalf of the buyer. The skinhead sports what we would call a Crombie, complete with ticket in the breast pocket.

Next up is a punk wearing the bondage garments initially designed by Westwood and McLaren for Seditionaries but quickly reproduced by BOY and then countless other market traders as they became a first-generation punk imprimatur. He tops this off with a low-slung bullet belt, studded dog collar and leopard print tee-shirt. The final two figures are a traditional teddy boy in a royal blue drape jacket with velvet pocket trim and a rockabilly who looks to be struggling to assert an identity. The date of November 1980 places it just prior to the mainstream emergence of new romantic, whose styles would most likely supplant the Bowie figures through 1981.

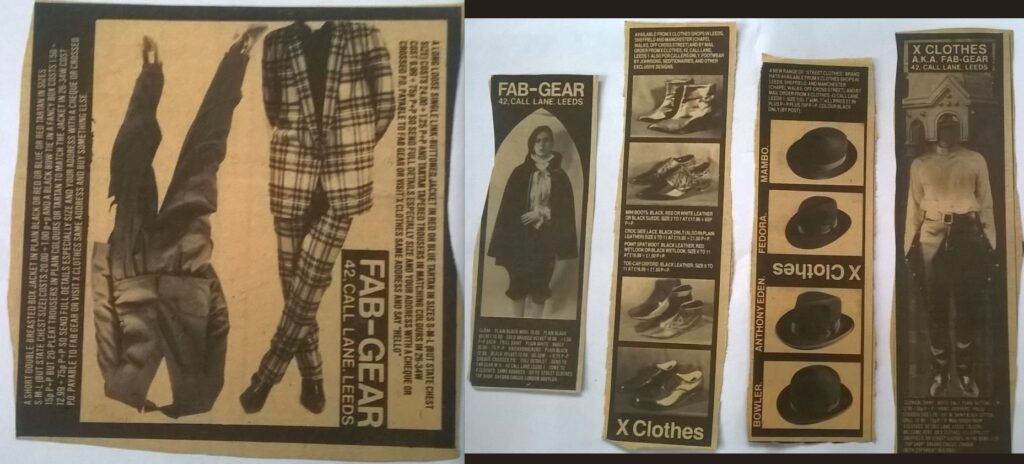

In the same vein, I recall having a particular fascination for the small advertisements for Fab-Gear (which morphed into X-Clothes). This was a boutique shop in Leeds, which I visited on later trips to see bands at The Warehouse or punk and post-punk weekenders at the legendary Queens Hall. I carefully clipped these from the newspapers and have kept them in a plastic wallet as they followed me through the subsequent decades. They clearly resonated with me.

They were obviously tuned into the subcultural strands of the late 70s and early 80s, generally employing photographs of the clothes being modelled rather than the untrustworthy drawings utilised by their competitors. It had a ring of authenticity. The photographs were predominantly cut-out silhouettes and arranged like a child’s dressing-up game, the heads of the models removed. I’m not sure why, maybe new romantic haircuts hadn’t made it north in 1980 or 1981. One example stands apart, a great image of an asymmetric haircut unfortunately spoilt by the model wearing a dreadful cape and frilled shirt, framed in a gothic arch. It is from March 1981, before the days that Leeds became a goth stronghold, giving the clipping something of an incunabula status.

The suit jacket advertisement, from February 1981, is another classic in an adventurous layout that fascinated me. It is arranged like a court card in a standard playing card deck with the figure both upside and downside. The advertisement has a tartan suit one way up and a cropped style new romantic suit the other way. It had an element of early PiL – John Lydon – who dressed so well with his quirky suits and slim frame. I spent long evenings studying this image.

Other advertisements in the music newspapers portrayed grids of punk tee-shirts in a numbered system, where you simply picked a design and hoped it looked okay and didn’t disappear in the wash. My own purchasing went as far as these tee-shirts, which were promptly posted to my suburban address, coming in a polythene shrink-wrapping with the shirt tightly folded into a ball so it fitted through a letterbox. To be fair, I got good wear out of them, twinning them with a cheapo PVC ‘biker jacket’ that came from a stall on Derby’s Eagle Centre Market. Some of these tee-shirts are evident in my parents’ holiday snaps, when I was in my early teens and tentatively trying to look punk against the twin current of a disapproving dad and having to sport a kitchen-as-salon haircut created by mum.

It would not be until 1978 that I started getting properly into punk, at its commercial height with major punk and new wave acts often dominating Top of the Pops around that time. Unashamedly, I was attracted to the picture sleeves and coloured vinyl that punk luxuriated in, having enough pocket money to just about fund my own journey. I have an indelibly etched memory of going to town on my own on the bus to buy ‘Hurry Up Harry’ by Sham 69 and ‘Ever Fallen in Love (With Someone You Shouldn’t’ve)’ by Buzzcocks, and being confidently assured that this was the first instance of an imposition of my own taste.

My slowly assembled punk uniform was anchored on a pair of tartan trousers – not a fancy branded pair from Seditionaries, but a pair from the ever-reliable Eagle Centre Market made by subcultural appropriators Crazy Face. These were matched with the tee-shirts and an unbelievably shoddy acrylic striped furry jumper in blue and white. This latter item, another Eagle Centre purchase, was a copy of a punk standard – it looked more like a fairground gonk prize trialling for QPR than a punk-fashionable mohair jumper. Somewhere in the mix was a brief period trying to wear punk string vests over my ‘Mr Puniverse’ physique. These vests, in a starched and thick weave that resembled a dishevelled mop head, could be purchased from army surplus stores – but I’m not sure any soldiers or sailors actually wore them? This assemblage was part provincial punk, part provisional punk. On top of this as my crowning moment of apparent individuality I had a jumble sale raincoat which I ripped and re-stitched, and fashioned with a union jack neckerchief.

Punk’s use of the raincoat was an example of taking a clothing standard from outside subculture and turning it to a new use or adding marks of destruction. The spoilt school blazer was another example of a punk standard drawn from ‘regular’ society. Both the blazer/suit jacket and the raincoat would migrate across to the first inklings of a post-punk uniform in 1979, but I was too naïve to appreciate such fashion dynamics – any cool post-punk aura (unlikely) was purely happenstantial. Anachronistic to the core, I embellished my ripped raincoat with the oversized and mirrored punk badges from seaside tat sellers and an old chain pull from grandma’s outside toilet. The trousers and raincoat had to be kept in a plastic bag and stashed in a hiding place. In 1979, when heading off to punk gigs at Derby Assembly Rooms, I got changed on the bus to town, out of sight of my parents. Like the repurposed bog chain, this is another punk myth trope that rings true in my own backstory.

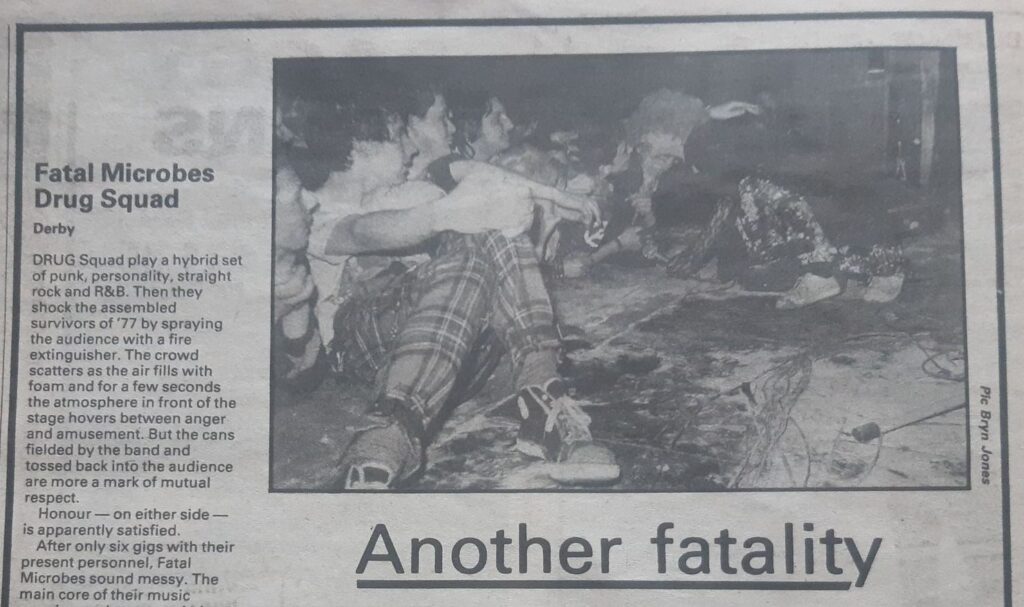

We had no cameras at this point in time, and this outfit worn in secret would not be immortalised in any family albums. However, a photograph emerged recently from the NME, part of a review of the Fatal Microbes appearing at Derby Ajanta in April 1980. I never got the NME religiously, so this review and photo passed me by, but (I think) the boy at the front is me. I do recall having bumper boots bought by my mum and also tying my cherished tartan trousers with bits of string to partly stop them getting muddy and partly to make them a bit more authentic punk. Even though it was de rigueur to give your clothes a destroyed appearance or patina, I was still obsessive about keeping them pristine and preserved into the future. My raincoat isn’t visible, but it would have been somewhere nearby. A document of a start, and evidence of a clothing fascination about to explode through the forthcoming decade.

– Ian Trowell