20 Jan 2026

Introduction

Karpowership is a Turkish company that designs, builds, and operates a global fleet of “Powerships” floating power plants that can be deployed to generate electricity for countries in need.

The company’s stated mission is to reduce energy poverty and support countries in their energy transition by providing a fast, reliable, and sustainable power source.

The Karadeniz Powership Doğan Bey is the first of its kind: a Powership equipped with dual-fuel diesel engines capable of operating both natural gas and heavy fuel oil.

Doğan Bey was first deployed in Basra, Iraq, where it operated for five years under a contract with Iraq’s

Department of Energy. After leaving Iraq, the vessel was redeployed to another region under a new contract. In late 2017, it began supplying power to Freetown, Sierra Leone. Karpowership has since suspended 50 MW of power supply from Doğan Bey off the coast of Freetown following longstanding non-payment issues.

layt de kam—which translates to “light is coming” in Krio—was a phrase Ibiye Camp often heard during power outages in Freetown, Sierra Leone. These outages frequently create communal moments of silence in a city otherwise vibrant and loud with the constant beat of sound systems.

layt de kam reflects the communal presence of the ship; it has become a figure in the West African landscape. Karpowership currently operates in Ghana, Senegal, Guinea, Gambia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea-Bissau. Several other countries in the region, including Nigeria, Gabon, and Cameroon, have been in talks or are potential clients.

Gökçe Günel is an anthropologist at Rice University, where she investigates how infrastructure transforms amid energy and climate change-related challenges. Her book, Floating Power: Energy, Infrastructure, and South-Relations, examines energy futures through the lens of Karpower’s Ayşegül Sultan.

Ibiye met with Gökçe in October 2025 for a conversation, offering two complementary perspectives on floating power plants.

“I was eager to learn more about the geopolitical arrangements and histories of these ships, which have captured my attention in an almost obsessive manner.” Ibiye Camp

Conversation

Ibiye Camp: When we first met, you mentioned ideas around monumentalism, and I’ve been thinking about this in a sense with the floating infrastructures. I was wondering how these powerships have reshaped local voices or international relations. In your work, there’s often an acknowledgment of tension. How do you show long-term instability within these infrastructures? Could this instability be described as a kind of infrastructural imperialism? And what have been the actual impacts on local communities and ecologies?

Gökçe Günel: The temporal horizons of these ships are quite fascinating. They arrive already anticipating their own obsolescence. When contracts are signed, there’s an emphasis that the ship is not a permanent solution; governments leasing them are encouraged to find long-term alternatives while the ship provides electricity.

In my book (Floating Power: Energy, Infrastructure, and South-South Relations), I describe how these ships are framed as liminal devices. They’re imagined as bridges between fossil fuel dependency and a renewable energy future, a linear progression towards “modernity.” But I also see them as what I call technologies of deferral. They extend the lifespan of fossil fuels by pushing the end of the fossil fuel era further into the future.

There’s also another temporal dimension: although the ships are supposed to be temporary, their presence often becomes permanent through long-term contracts. The “provisional” becomes embedded, absorbing national resources that could have gone toward alternative energy infrastructures.

One of the most striking aspects of my research has been observing the impacts of ‘take-or-pay’ contracts. In Ghana, for example, these agreements mean that the government pays for the ship’s full output, even if it doesn’t use all the electricity. So, even during low-demand periods, payments continue.

These contracts can last up to twenty years, creating economic burdens that make it difficult for governments to invest in sustainable alternatives. I should add that these contracts are by no means unique to Ghana or to Karpower: they are common across the Global South, especially in extractive industries and infrastructure projects. Once a take-or-pay contract is in place, the seller receives guaranteed revenue, while the buyer secures access to supply and can rely on future price stability. And it is well-known that contracts can lock countries or utilities into over-supply or unfavourable prices, but for many of the governments that accept these deals, there is little room for negotiation. So while the ships appear mobile and temporary, contractually they’re locked in, their formal flexibility undermined by economic permanence.

“So while the ships appear mobile and temporary, contractually they’re locked in, their formal flexibility undermined by economic permanence.” Gökçe Günel

IC: In some of your writing, you reference forms of imperialism taking shape in West Africa. I’m also interested in the symbolism of the ship itself, as a visual and historical form. On the West African coast, especially, the ship seems to carry a heavy legacy.

GG: Absolutely. The ship is a powerful symbol, especially along the West African coast. Historically, ships were tied to colonial extraction and the transatlantic slave trade, transporting raw materials and enslaved peoples.

In describing the relationship between Turkey and African countries, one historian used the phrase “imperialism by anti-imperialists,” mainly because Turkish government representatives often use critiques of imperialism as a way to form relations with countries such as Ghana. But obviously, Turkey is not the only foreign government supplying services to Ghana. For instance, when I conducted fieldwork in Tema, Ghana, the floating power plant was anchored near Chinese fishing vessels that were extracting fish from the same waters. Various Chinese companies have also built solar power stations in Ghana, as well as dams and even floating solar installations. In one case, a solar plant was followed by a sugarcane plantation, powered by the same electricity, with promises of domestic sugar production.

So you have solar plants, symbols of the renewable future, existing alongside sugar plantations, symbols of colonial labor. These contradictory timelines of “progress” and “past” coexist, shaping one another. It challenges the linear narratives of development that many people rely on and reproduce.

IC: That’s a really important point. For me as an artist, the ship becomes a way of unraveling these overlapping structures of control, extraction, and power that coastal countries have historically faced. The ship isn’t just about energy; it’s about what its presence reveals in the landscape.

GG: Exactly. The ship is part of a wider ecosystem, material, political, and symbolic.

IC: When my collaborator, Rihanna Dhaliwal, and I went to Tema, we searched for the ship. People kept saying, “It’s just around the corner,” but we later learned it had already moved; it had left in 2019. It felt almost hidden, removed from the landscape, which contrasted with my experience in Freetown, where the ship is a visible part of the city’s horizon. This made me think about visibility. Initially, the powerships were heavily publicised, almost celebrated, but has that changed over time? Has Karpowership become more secretive?

GG: I assume it’s different in each context. In 2015, as soon as Ayşegül Sultan left the Turkish coast, the Ghanaian media started tracking its progress. They were anticipating its arrival in Tema. Some commentators issued warning calls, asking politicians to review Karpower’s history in Lebanon and Pakistan. They wanted to understand the possible financial impact of the ship on the country’s economy. But representatives of Karpower believed they could be kingmakers and that they could facilitate the incumbent President John Mahama’s reelection. In 2016, the Karpower ship appeared in Mahama’s election campaign posters, even though it eventually did not help him gain victory. Even after Mahama’s presidency, the updated agreement Karpower signed with the Electricity Company of Ghana in 2017 indicated that the ship would supply 470 megawatts of electricity to the Ghanaian grid for a whole decade. The ship’s formal ability to sail away became secondary to contractual obligations. In 2023, when I asked an executive at the Energy Commission in Accra what he thought of the Karpower ship, he answered, “It is the story of how the provisional becomes permanent.”

IC: In Freetown, the powership almost became like a character. People would talk about it as if it were a person, wondering whether it would go or stay. Someone once called it the ‘powerhouse’, and I even heard it described as a ‘powerbody’. That language really fascinated me, the way the ship became this visitor, or even a kind of being. When I was looking through your research, I noticed you mentioned Karpowership’s slogan, “The Power of Friendship.” When I looked back at my own photographs from Freetown, I realised that some of the small boats taking workers between the ship and the shore had that slogan painted on them.

“In Freetown, the powership almost became like a character. People would talk about it as if it were a person, wondering whether it would go or stay.” Ibiye Camp

At first, I thought it was just decoration, like how local canoes often say “In God We Trust” or carry football team names. But then I started thinking about how that kind of language, ‘The Power of Friendship’, ‘the powerhouse’, ‘the power body’, forms its own vocabulary around the ship.

You mentioned ‘Dumsor’ (power outages in Ghana, derived from the Twi words “dum” (off) and “sor” (on) in your writing, and I was wondering whether you’ve come across other kinds of language that have emerged from the presence of these visible infrastructures. How do ships like these begin to affect everyday language or slang in the places they appear?

GG: That’s such an interesting question. One thing that struck me was the naming of the ships themselves. The first ship I visited in Tema was called Ayşegül Sultan. Later, it was replaced by another ship called Osman Khan. Many of these ships are named after members of the family that owns the Karpowership company; it’s a family business, and naming ships after relatives is a way of honoring them. Sometimes, employees who have been particularly dedicated are also rewarded by having a ship named after them. One ship engineer I interviewed was very proud that, even though he wasn’t part of the family, a ship carried his name. So within the company, it constitutes a reward structure, a way of extending someone’s presence globally through these vessels. At the same time, these names evoke an imperial sensibility. In contemporary Turkey, people don’t usually refer to one another as Sultan or Khan, so the names recall the Ottoman Empire, when state representatives were deployed to govern different regions. In that sense, each ship becomes a representative to a vassal state, a small node of empire asserting its presence in another land.

IC: I remember from our previous conversation that you mentioned how sometimes governments compare themselves: “You have a ship, so I want a ship too.” It becomes a kind of status marker, almost like having the latest iPhone, a symbol of being technologically current.

GG: Exactly, it’s a kind of geopolitical trend-following. The ship becomes both a tool and a statement of modernity. I was really interested in hearing what you think the ships represent. You began by describing them in terms of monumentality. What do you think they are monuments to?

IC: The ships, to me, symbolize a kind of loophole. I understand that at sea, you can use the national flag to fly, allowing you to bypass certain laws. So I think of the ship in Freetown, about 500 meters from the shore, as existing in a sort of in-between space. It feels like it runs on its own offshore agreement or contract, and that sense of uncertainty becomes symbolic for me.

I also connect this idea of the loophole to something futuristic, an Afrofuturist imagination. The ships remind me of narratives in science fiction, existing outside of ordinary governance or space. They’re on another plane of control, beyond the land.

GG: I really like that, the idea of the offshore as a space where extractive work can happen. The ships in Ghana, for example, carry Liberian flags of convenience, which is quite common across the shipping industry. It’s not about nationality but about avoiding taxes and easing registration. Even so, they’re not in international waters; they’re still governed by Ghanaian or Sierra Leonean laws where they operate.

But I do see what you mean, the ships have a kind of Afrofuturist sensibility. Many people have told me they look like Mad Max, salvaged parts fueling the future. They’re not shiny or new, but practical, reusing old ships with new engines to serve places with unmet demands.

“…the ships have a kind of Afrofuturist sensibility. Many people have told me they look like Mad Max, salvaged parts fueling the future. They’re not shiny or new, but practical, reusing old ships with new engines to serve places with unmet demands.” Gökçe Günel

IC: Yes, the secondhand aspect fascinates me too. When I was in Takoradi, I noticed many naval ships were from the Second World War, Japanese ships, with the writing still visible. There’s something about these secondhand vessels, these remnants from elsewhere, being repurposed in Africa that really stays with me.

GG: That’s interesting because the ship operators, like Karpowership, are aware of that perception. They emphasize that, while the ships themselves may be old, their engines are brand new, mostly from Germany or Finland. Many of their ships were actually bought after the 2008 financial crisis, when ship prices collapsed. I’m also curious about how you learned about these ships from the communities around them. My own research focused more on energy experts, people connecting the ships to the grid, so I’d love to hear about your conversations with everyday people.

IC: Most of my conversations were in Freetown. I don’t remember much about when the ship first arrived, but people talked a lot when the power output was reduced by around 60%, I think, because of unpaid bills. Where we live, power outages are quite memorable moments. The city is so loud, music, sound systems, so when the electricity goes out, there’s this rare quiet. I remember sitting on the balcony and hearing someone say, “Layt de Kam!” That phrase, “light is coming”, really stayed with me. It carried a kind of optimism that contrasted with the uncertainty surrounding the ship. In Koo Bay, one of the closest communities to the ship, I photographed a few men sitting and watching it from the shore. Even though it’s there every day, it remains mysterious. People call it the powerhouse and speak of it through hearsay, stories about it shutting down or leaving. Over time, those stories have become more anxious, especially as electricity access has become less reliable. Some areas in Freetown have been without power for weeks now.

“The city is so loud, music, sound systems, so when the electricity goes out, there’s this rare quiet. I remember sitting on the balcony and hearing someone say, “Layt de Kam!” That phrase, “light is coming”, really stayed with me.” Ibiye Camp

GG: I also wanted to ask about the medium you use to represent these ideas. I live in Houston, walking distance from the Dan Flavin Installation at Richmond Hall, which always makes me think about post–World War II art and its relationship to electrical abundance. In your case, you’re dealing with electricity as a scarcity. You’re not using electricity as the medium itself but rather employing vernacular methods to represent it. Could you speak about that choice?

IC: That’s interesting, because in some ways I am using electricity to laser cut the fabric. There’s a tension in the work between traditional and technological processes. I dye the fabric using kola nuts, a traditional West African method, but then I laser cut the dyed material, which involves concentrated light and power. I see myself as someone who works with technology, but I’m also cautious of it. I’m drawn to both traditional craft and new tools, scanning, LiDAR, while questioning how we live alongside machines. This project, for me, bridges those tensions.

There’s also an influence from artists like Martin Creed, his ‘Work No. 227: The lights going on and off’ always resonated with me. My mother used to joke, “In Nigeria, that’s just a power cut!” But I find that piece profound in its simplicity; it captures the rhythm of contemporary life, especially in places like Sierra Leone, where power cuts punctuate our days. In my Kalabari tradition, fabric holds stories; it’s a medium for communication. By combining that with scanning and cutting technologies, I’m exploring how to merge West African textile practices with architectural and digital tools in a way that empowers both.

GG: That’s fascinating. Your work sits within a larger history of art’s relationship to electricity, sometimes representing it, sometimes using it as a medium. Even when it’s not visible, it’s embedded in the process.

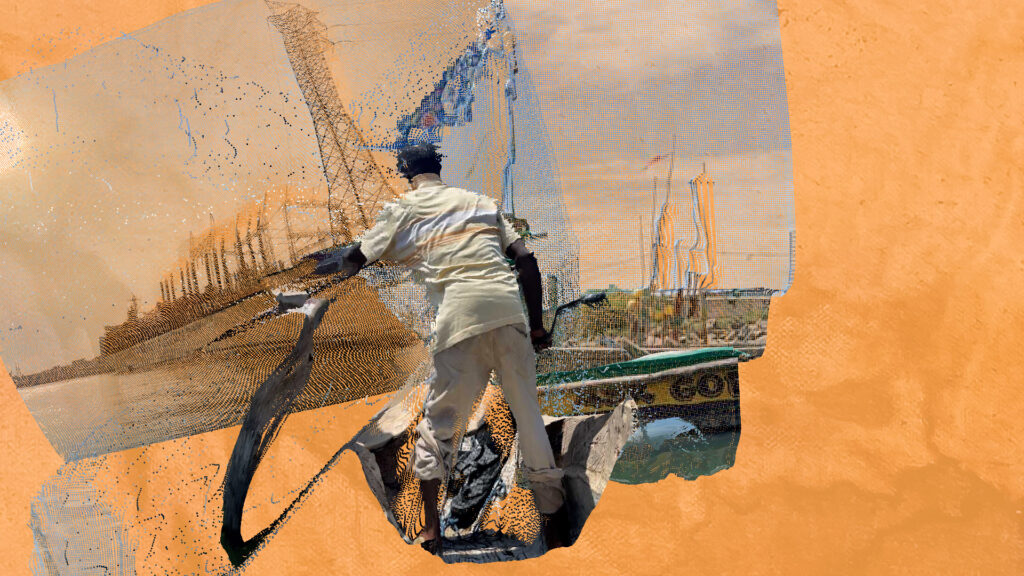

IC: Exactly. When I worked in Sierra Leone, I was scanning markets and had to render the 3D files at very low resolution because power was unpredictable. I never knew when electricity would be cut off. So the time and access I had directly shaped the outcome. That’s something I’ve come to appreciate: how power availability literally determines the form of the work. The low-resolution scans from Sierra Leone carry that constraint as a kind of signature, while the high-resolution works made in London reflect a completely different energy context.

GG: That’s a beautiful way to think about it, electricity as an invisible signature within the work, marking place, time, and access.

Images taken from Ibiye Camp’s new film GLOW (2025), presented within her solo exhibition layt de kam at Bonington Gallery, January 17th – March 7th, 2026.